Readings: Hà Nội in the Old Days, Pt. 4 - Education

Today's article may seem a little dry, but I found these chapters to be very insightful for developing a deeper understanding of French colonialism in Việt Nam - of day-to-day life - and the profound effect it had on the culture here, especially in Hà Nội itself.

The author adheres to traditional Vietnamese values about the importance of filial piety (respect for parents, elders, and ancestors). Many of the following chapters include lists of important and famous people associated with these schools; I have not included these as it is outside the scope of my summary. Many of them have later chapters devoted to them, so this section can be said to lay the foundation to understanding the background of people who will drive the rest of this book's 'narrative', the lifeblood of Hà Nội.

The translation methods used are hasty and poor quality; anything written here should not be taken as well-researched fact. Each section below represents a chapter in his book. This is only summary, and I have tried to capture the flavor of the writing, purely for my own edification.

Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục School

The Trường Đông Kinh nghĩa thục, or Đông Kinh Righteousness School, established in March 1907 is a model school of patriotism.

The city of Hà Nội (meaning 'inside the river') has had many names in its history, including Long Biên (meaning 'entwined dragons'), Thăng Long (meaning 'ascending dragon'), and Đông Kinh (meaning 'eastern capital'). This last name was the source of the French colonial name for northern Viet Nam: Tonkin.

The founders were patriotic scholars. After visiting Phan Bội Châu in Japan in 1906 they modeled their school after Keiō Private University which was called Trường Khánh Ứng nghĩa thục in Vietnamese.

The location at 4 Hàng Đào was in the midst of a bustling commercial street (in the present-day Old Quarter) specializing in velvet, silk, and wool with merchants from China and India. Many famous Vietnamese scholars came out of this school.

The finances came from the teachers themselves and from private donors. The education included Chinese and Western studies. The Writing department compiled textbooks on National Identity, National Literature, Vietnamese Geography, Ethics, Western Civilization, and translated Montesquieu, Voltaire, and Rousseau into Chinese.

The Propaganda Department called on all people to have patriotism, to remember their origins and shared ancestors, and unite to love and protect each other. They believed a country with a rich culture would be strong and free from slavery. Their viewpoint was to train people to be useful to their country: to emphasize practical work and live a new way of life. They valued wearing short shirts, short haircuts, keeping teeth clean, using domestic products, and eliminating "bad" customs and superstitions. In addition to fighting "backwards" ideology, they wanted to cultivate a progressive bourgeois class like the ones they saw in Japanese or Western society.

The school organized 8 classes during the day and evening. Students did not have to pay tuition. Students who already know Chinese study French. The ones who already know French study Chinese. The number of students ranges from 400-500 and includes students of all ages, even the elderly. There is a library with new books and newspapers, and it is open to the public.

The political purpose of the school was clear. In November 1907, the Mayor of Tonkin urgently dispatched to the Governor's Palace that the school was openly attacking French rule. The school was ordered to close, and within days it was shuttered. (It lasted well under a year.)

Many of its members were sentenced to hard labor or exile. Public opinion was ablaze with fury, and after the poisoning incident in 1908 strikes and protests broke out. The French government was forced to reduce the sentences.

Other texts state that the teachers of the school were arrested after the poisoning incident and acts of rebellion in 1908. I'm not sure whether this discrepancy represents a failure of my understanding of the text, or the text having an alternate view of the history.

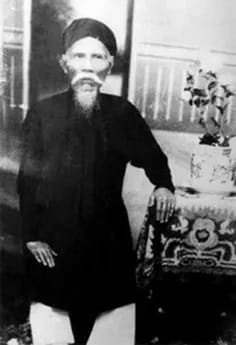

Co-founder Lương Văn Can was allowed to return to the city in 1921 after eight years in exile. Undaunted, for the rest of his life he contributed to the world by writing and compiling books: studies of Chinese language and literature, Espionage, Instructions for Families, and Early Childhood Studies. He refused to become an official.

His virtuous wife helped him raise eight children. Five sons preceded him in death fighting for their country. He passed away in 1927 at the age of 73. His funeral banner read: "Loyalty and filial piety are the most important things. Everyone should follow these words in life."

Education During the French Colonial Period

To help the French government in the colony, they opened a post-secondary school for language to help with communication. A convent school was opened in order to propagate Christianity. By 1907, eight primary schools had been opened in Hà Nội. In addition to the public schools, there were eight private schools and three girls' schools.

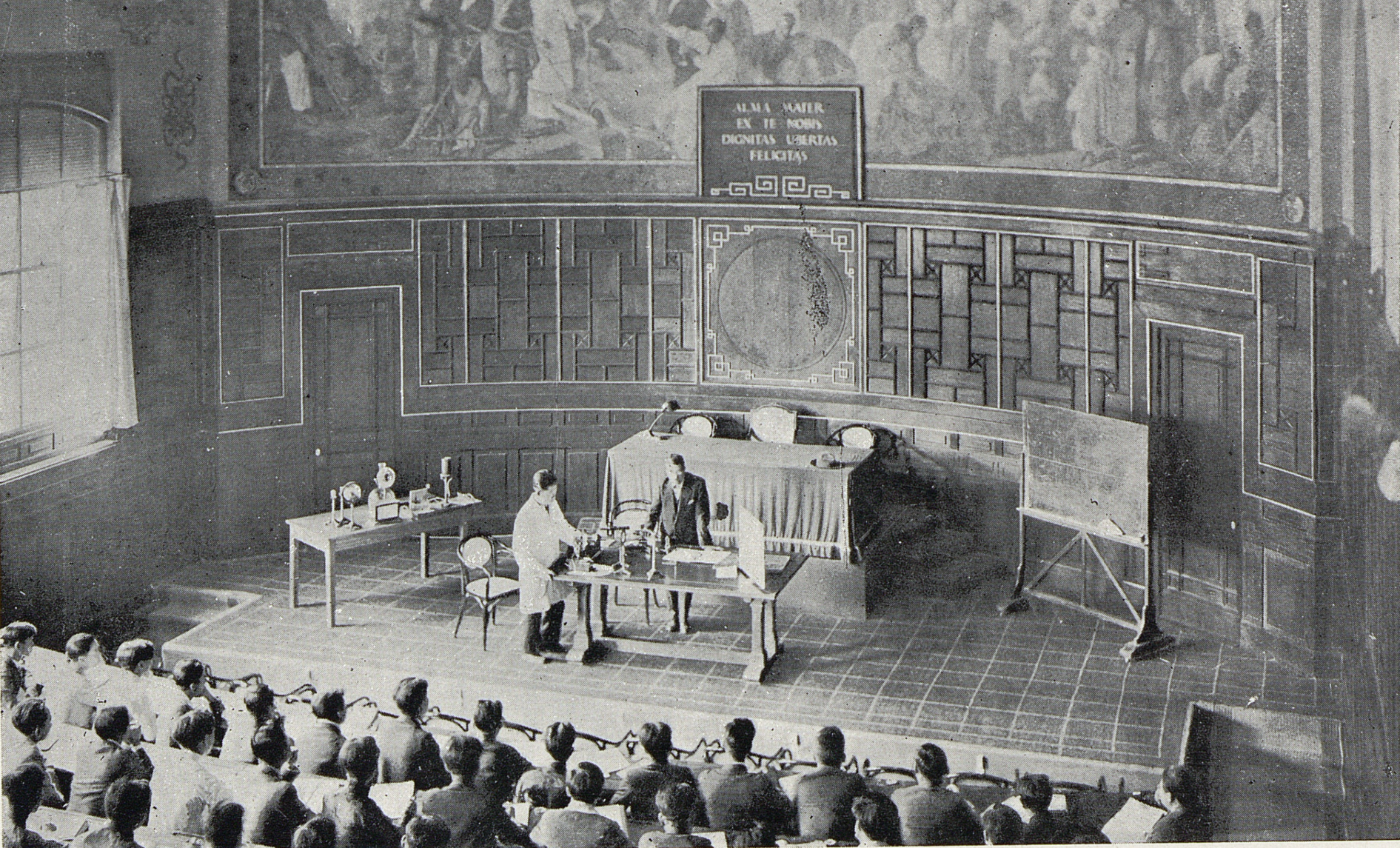

In addition to the primary schools there was a secondary school, called Bưởi School, whose true name was the Lyceé Protectorat du Tonkin. There were professional schools devoted to agriculture, teacher training, public works, and practical technology. The Indochina School of Fine Arts taught painting and sculpture. The School of Commerce taught trade and accounting, holding its first classes at Bưởi School. In 1917, a college was opened with faculties in medicine, pharmacy, architecture, and law.

In 1930, village chiefs in rural areas were required to have a certificate of an elementary education. After primary education, four years of high school qualified you to take the high school exam; this diploma certified that you could speak and write French fluently. With this diploma and two additional years of high school, you were qualified to take university entrance exams.

In order to enroll in the schools, you needed a birth certificate. In the early years, parents had to worry about creating some kind of birth certificate. The ages were sometimes not true. Students who were admitted were listed in the newspaper!

Elementary students had to learn French right away. Numbers were called for roll instead of names, and students had to answer in French. Every week there was an ethics lesson to teach respect for your family members, elders, and to love teachers. Vietnamese history is only taught for the first two grade levels. Afterwards, students study French history exclusively; when they graduate they know it better than their own country's history.

Bưởi High School in its Early Years

The Lyceé Protectorat du Tonkin, also known as the Bưởi (Pomelo) School, was established in 1908. In the past, 100m from the school gate was a shop selling snacks and cakes next to a tall cotton tree. Before school, students gathered to eat snacks in the shade of the trees of the school yard.

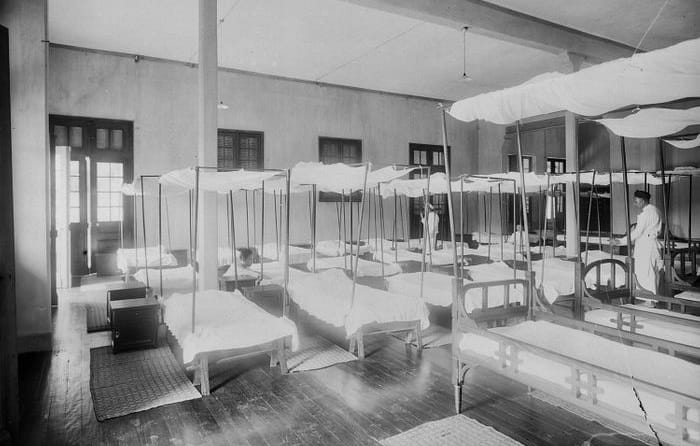

The first class of the school accepted 400 students, 200 students as boarders. Students who score highest on their entrance exams receive a monthly scholarship of 4 VND; the fees for food & accommodation in the dormitory equal 8 VND. The teachers were mostly with French, with only a few Vietnamese.

The dining room and bedrooms were airy and clean; the bathrooms had not yet been built, so students bathed in wooden barrels near the lake. School rules forbade students from bathing in the lake for fear of accidental drowning. Every student had to buy a bell-locked chest, a bronze basin, an enameled iron mug, and had to supply their own wooden clogs. The pens were wooden with iron nibs; fountain pens were too expensive. Bicycles were rare; students who lived far away took the train.

Boarding students were only allowed to go out to play for a few hours on Sundays, but like birds out of a cage many couldn't come home in time and had to sneak back in over the wall. Students were all boys; girls at this time were mostly illiterate until the first girls' schools were opened.

In 1910, Indochina held an examination to select four high school students from Hà Nội or Hải Phòng to study in France. All four were selected from Bưởi School, and these students were called the "Four Tigers of Tràng An."

The Founder of the Indochina College of Fine Arts

In 1939, on the 2nd anniversary of Victor Tardieu's death, everyone stood in a line around a statue of him on the school's grounds laying bouquets of colorful flowers at his feet.

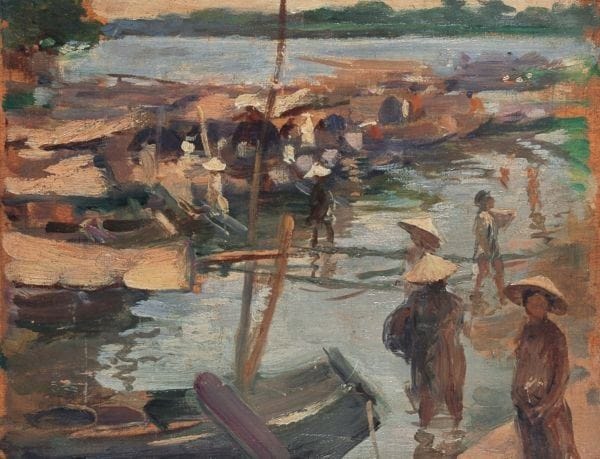

Mr. Tardieu was an exemplary man. Far from his wife and children in France, he came to consider Việt Nam his second homeland. He had a kind face, white hair, and a cane in hand. His students flock around him; teacher and students love each other like a father and his sons. On his days off he would pack a portable easel, go out to the countryside and paint all day.

He fought to keep the school alive only five years earlier; the Indochina Congress wanted to fold the school into the Polytechnic school, seeing a separate Fine Arts school as a waste of money. But he fought them, and one evening knocked on each student's door to share the news: "They won't close the school anymore." The students hugged him in joy.

It was a hot summer and he should have gone on vacation, but for years he had been absorbed in his work. He fell ill and was admitted to the hospital, but he died two days later, at age 70. He laid the foundation for Vietnamese painting. It is thanks to him that we have the famous painters we know.

The Indochina School of Fine arts

For a long time, Vietnamese painting fell into a slump because there was no training. Dong Ho and Hang Trung style folk painting had nowhere to develop to.

The college was founded in 1925 in a small house with a metal corrugated roof (near the Maurice Long Museum). Governor Varenne wondered why it should exist as a separate school. Tardieu said: "That is a short-sighted view. A country that is called civilized but does not develop its culture is shirking responsibility. If you want France to be glorious, you need to cultivate talent in the colonies."

A course lasted five years. From the beginning to the school's end there were 15 classes, each with about 10 artists. Mr. Tardieu advised them: "Study to know, but do not copy. Western painting should only be a reference. In the East, you should learn from China and Japan and preserve your new national identity."

In 1943, the US bombed the area and the school had to evacuate to the Temple of Literature. Many famous painters graduated from this school and created Việt Nam's rich art heritage, innovative in many media: oil paint, lacquer, watercolor, Chinese ink, and silk.

Northern Association for Mutual Education

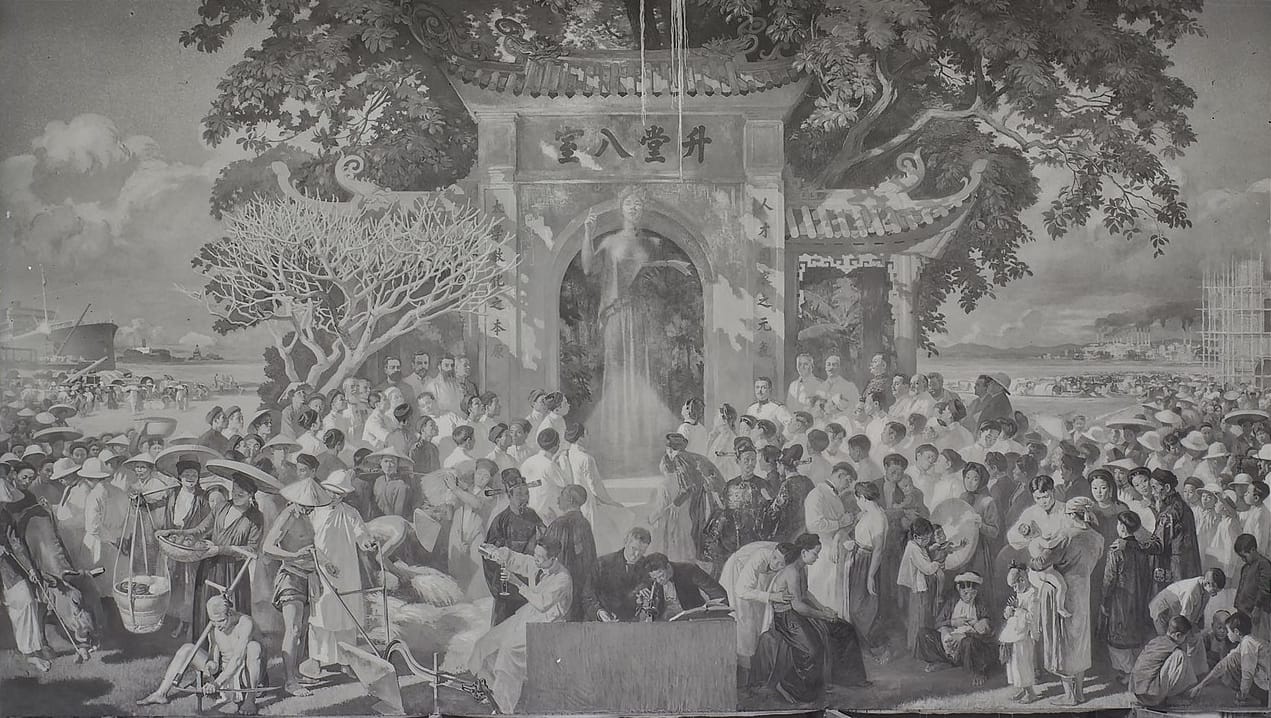

La Société d’Enseignement Mutuel du Tonkin was established in 1892. At first it was just a small, narrow, one-story house, but later thanks to donations it was completed as a two-story house in Chinese architectural style. There is a plaque there still engraved with the French name, and the French who contributed to its founding, with Governor Paul Doumer at the top of the list. Below these names are the names of 108 Vietnamese people, in Chinese characters.

Hội Trí Tri, the name of the group in Vietnamese, comes from a Han dynasty idiom "cách vật trí tri" which concisely describes seeking both knowledge and deeper understanding (or wisdom). The purpose is to attract intellectuals of both Confucian and Western backgrounds, promote understanding of each other, and to promote the use of French in Northern Việt Nam. It would later expand into various nearby provinces.

Classes are held Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, from 20:00 to 21:30, to supplement the education of those over age, or otherwise unable to complete a public school education. There are about 95 students at first. The association organized a committee to translate French and Chinese books. At first, few people believed in translation, but Vietnamese proved able to hold profound philosophical thoughts from the great literary works: Les Trois Mousquetaires, Les Misérables, La Peau de chagrin, Le Bourgeois gentilhomme...

In addition to studying, students have to exercise, because poor physical health is not only harmful to oneself but a burden to society. Behind the clubhouse, banana and cassava plants were leveled to make a training ground. A single bar made of ironwood for chin-ups, a few dumbbells, a pole, a coil of rope, and a few wooden rackets. A westerner teaches general physical education, while a Vietnamese teacher teaches martial arts (using staff, fist, or sword).

The lectures were usually in French and covered topics such as language, ethnology, hygiene, and general science to help attendees understand foreign literature, how to maintain health and prevent disease, and how to conduct business and accounting. Those invited to speak are experienced professionals.

The National Language Propagation Association was created here in 1938. Classes were opened all over the country, leading to the elimination of illiteracy. The school was also an important revolutionary site. In 1945, the Việt Minh met there to plan the uprising on August 19 (the August Revolution) and organize the event for President Hồ to read the Declaration of Independence on September 2.

The Sports School of Old Hà Nội

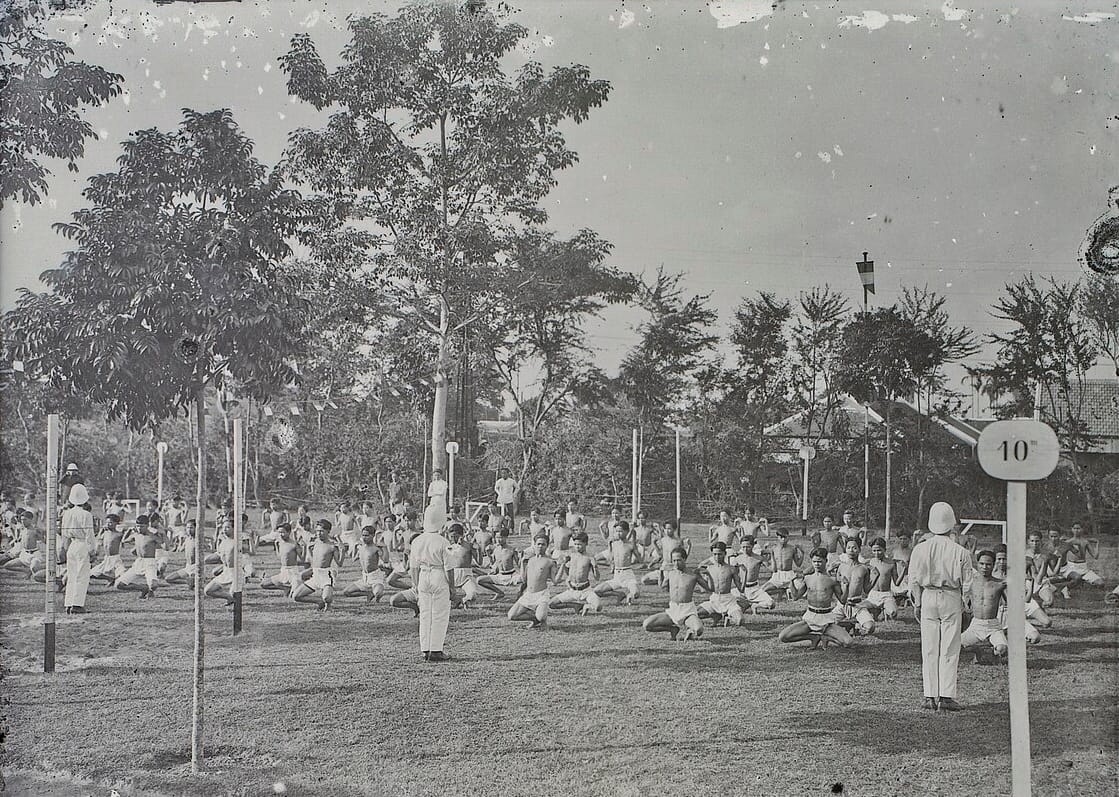

The Ecole d'Education Physique was the first school in Việt Nam to train physical education according to Western methods. The school was inaugurated in December 1919 by Nguyễn Quý Toản, a mandarin who loved sports, and was paid for by the colonial government.

The location was a large open field on Tô Hiến Thành street between shabby, thatched houses. Participants wore red loincloths, some of them came from the city just to train here for a while each day. Besides climbing ropes and weights, there was a running track and a concrete tennis court. Every day at 5:00 am, the door opens and a large number of young people come to practice freely. They practice so enthusiastically that many don't leave until the city lights are turned on at night. Not having any rackets, the students carved their own from wood.

In the 1930s, the southern part of the city expanded and the school was demolished. There is no trace of it left on Tô Hiến Thành street.

The Private School of Thăng Long

The school was founded in 1928, and the students studied very hard and always got high scores on their exams. They skipped gym sometimes. In 1933, they moved to a bigger school, but the classrooms were still cramped. Everyone at the school felt like brothers responsible for each other. In 1935, the new school was completed and the school passed a turning point.

In order for the school to exist and operate for a long time, a group of teachers established the "Association for the Development of Private Education" which was innocuous and made the colonialists less suspicious. There was a scholarship fund for poor but good students.

The policy for the school followed the model of Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục School, to guide students to have patriotism and hatred for colonialism. Lessons that might be regularly taught - such as French history - are glossed over in favor of revolutionary ideas. On holidays, the school often organized field trips for students to increase morale. Many times, teacher Võ Nguyên Giáp took students to the tomb of Francis Garnier or Henri Rivière so that the students could see the heroic feat of our people killing French leaders.

Võ Nguyên Giáp would go on to become one of Viet Nam's most important generals and military minds. He is often the 2nd historical figure that my Vietnamese colleagues ask me if I know about, after Hồ Chí Minh.

A large number of students started participating in revolutionary activities such as distributing leaflets, and the Popular Front (1936-1937). Many students joined revolutionary ranks and would wind up in important positions in the party or government. The day after National Resistance Day (December 20, 1946) French tanks opened fire on the school.

One of the school's former students reopened the school in the 1950s, and it would soon garner the favor of President Hồ. It would become a model for educational reform and one of the top primary schools in the city. It was later awarded the title "Thăng Long Heroic School."

In the next edition: A trip to the botanical gardens and the market