Readings: Hà Nội in the Old Days, Pt. 2

I have embedded several videos this week, in order to present a more visually immersive version of this survey of Vietnamese history and culture. When reading this in your email, these videos annoyingly function as a link which closes your email and opens up a separate browser window. If you would like to keep the video and text on the same page, you can read the newsletter on the website by clicking on the title above, or the small text underneath that says "View in Browser".

I have also updated the first issue of this series with two videos from Youtube that showcase some things that I was not able to provide pictures of: Bích Câu Temple and an example of ca trù singing, if you are interested.

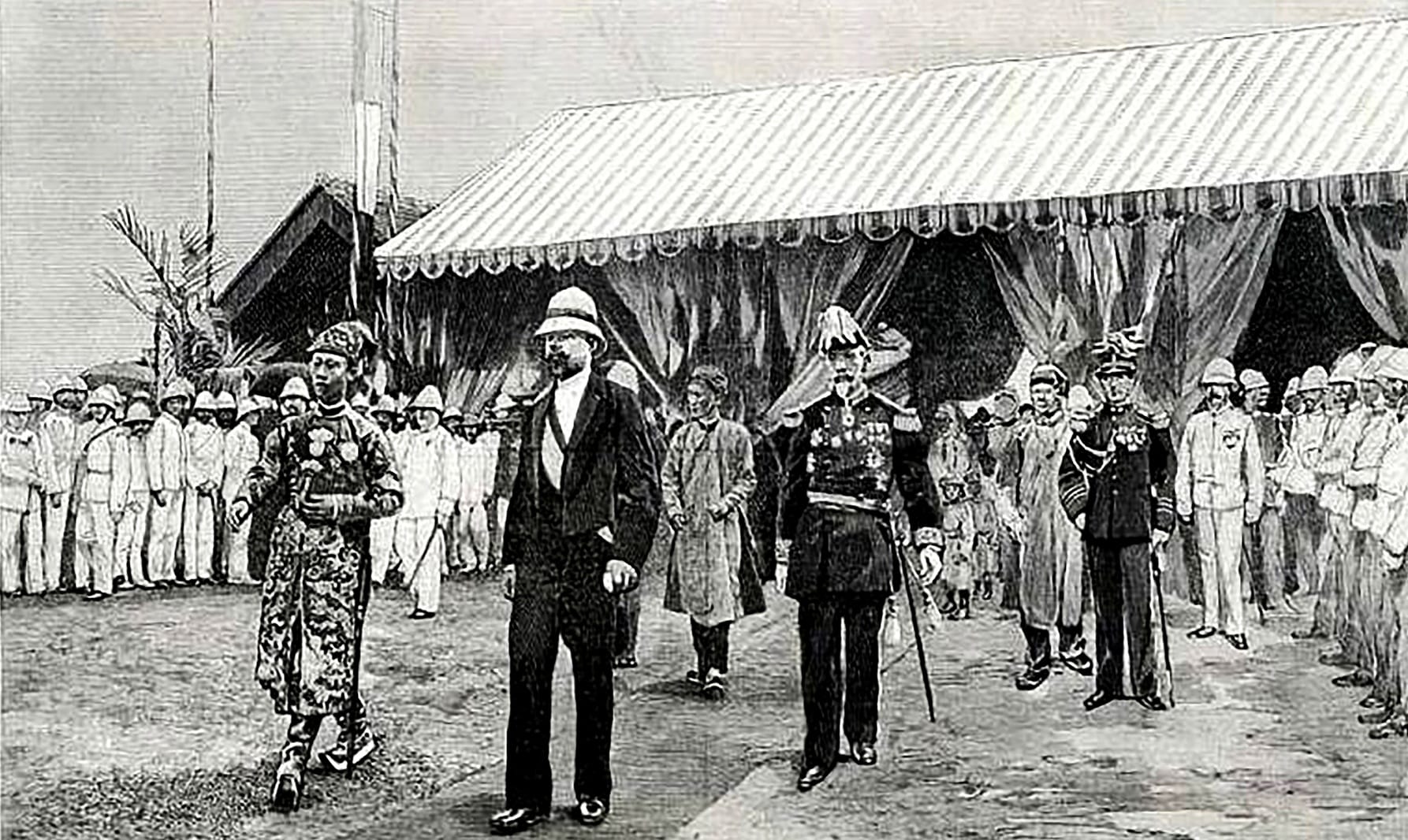

King Thành Thái Attends the Opening of Paul Doumer Bridge

The iron bridge across the Red River surprised many people in the early 20th century. In the past, whenever there was a trip from the capital to the Kinh Bắc region, people had to wait for a ferry. It took half a day to cross the river, longer in June and July during the flood season. But it was a very important traffic route.

Paul Doumer, Governor-General of Indochina, submitted the plans to France for approval. The bridge would be 1,800 meters long and cost 6,200,000 francs. From 1899 to 1902, about 400-500 people worked every day to build it: 21 stone piers, horizontal and vertical beams of pre-cast iron, and a deck made of ironwood to accommodate cars and trains.

The French were proud of this unique achievement, and Governor Doumer invited King Thành Thái from the court of Huế to attend its inauguration. The king was 24 years old at that time. On the roads that the king passed, poles were erected with the Tam Tài (Three Talents) and Ngũ Hành (Five Element) flags. At the foot of the bridge coconut leaves, lanterns, and paper flowers adorned it. Officials stood on both sides to welcome him in bronze or purple uniforms.

Bystanders wanted to see the king's face but were made to stand dozens of meters away. Houses close to the sidewalk were forced to close their doors, so people removed tiles from their roof and stuck their heads out in order to see. People waited from early morning until the sun shone high in the sky.

Finally at 7:55, four shiny black open-top cars appeared. In the first car was the governor, wearing a hat like Napoleon's, a long cloak with brocade and a sash around his shoulders. King Thành Thái wore a yellow turban, a long yellow brocade robe with dragons and phoenixes, red pants and shoes. They were flanked by 20 mounted cavalry dressed in green and red with polished boots and brass buttons, one hand on the reins of their horses, one hand raising their swords high.

Twenty-one cannon shots rang out, followed by a band playing the French National Anthem. There was a short speech, followed by ribbon cutting. The king was invited to get out of his car to observe the bridge. After the cars passed over the bridge, it started to rain hard, but everyone remained there as it poured until the king was gone.

The Hà Thành Poisoning Incident

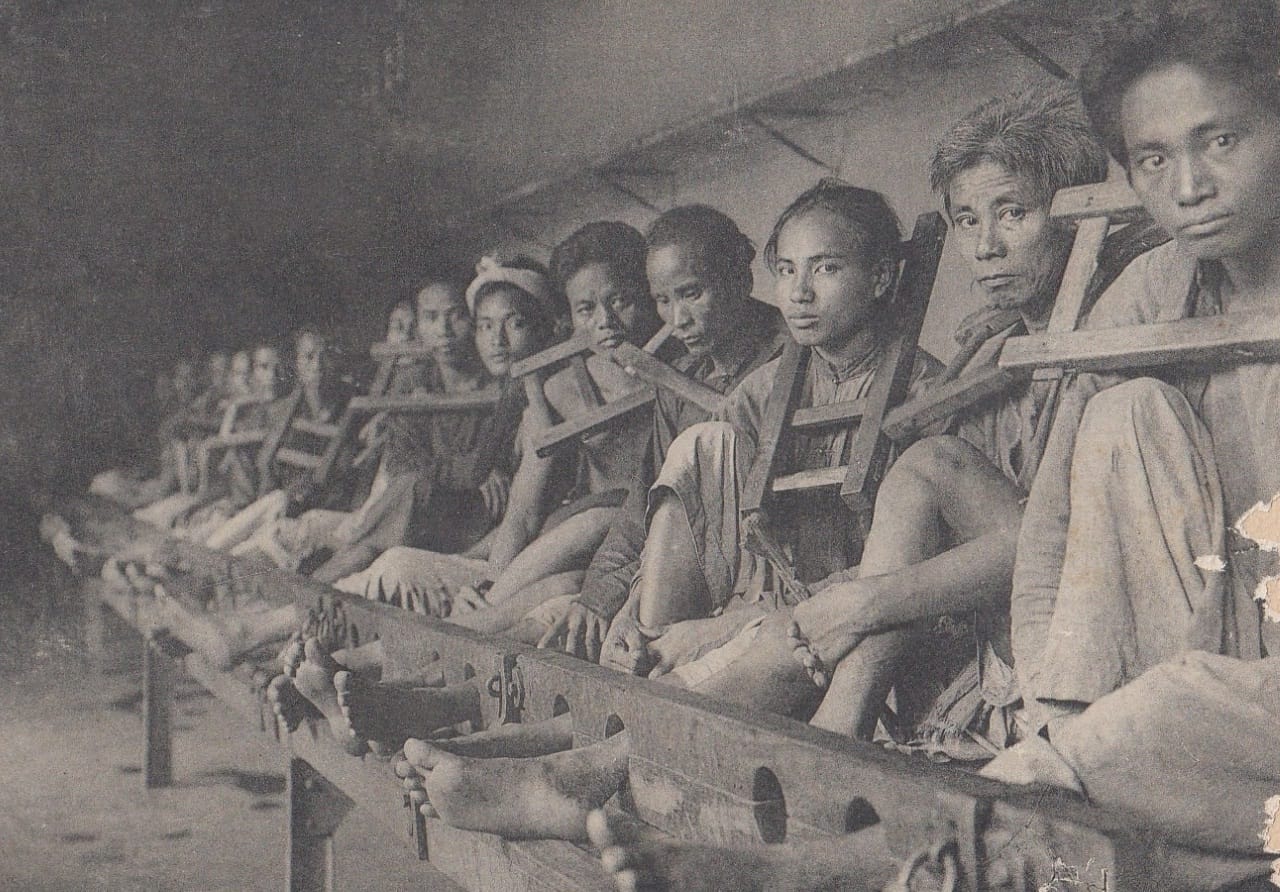

On a hot summer day in 1908, more than 200 French soldiers at Thăng Long Citadel suddenly fell sick after dinner. The mildly affected felt nauseous or had convulsions, others fell unconscious or immobile. An alarm was quickly sounded and the Vietnamese soldiers in the camp were disarmed.

The very next morning, one of the conspirators - who was Catholic - went to Hà Nội Cathedral to confess to helping poison the food. Father Ân immediately called Lieutenant Delemont Belet, and an investigation was carried out. The conspirators had met at a restaurant near Cửa Nam Flower Garden; scholars started meeting there to organize resistance after the French closed Dông Kinh Nghĩa Thực School in 1907. Phan Bội Châu's patriotic poems were brought in from overseas to mobilize people. There had also been a victory in the Yên Thế area which brought news of Vietnamese soldiers in the French Army defecting and bringing guns and supplies.

The uprising plan had an internal attack and an external attack. When the poisoning occurred, the cannons inside were to be taken over; three cannon blasts would then signal to rebels outside. These cannons never went off because the attack failed, and the reinforcements hiding in houses outside the citadel quietly slipped away when they realized their plan had failed.

Using brutal torture, some of the conspirators fell into the hands of the enemy. Four were sentenced to life imprisonment and hard labor, thirteen were sentenced to death. One of these, Mr. Nhiêu Sáu - the owner of the restaurant - escaped. His wife was tortured but never confessed anything; she died a few months later.

On the morning of July 8, 1908, gongs echoed and three chained prisoners were paraded behind foreboding executioners with heads covered in axe-head scarves. People flocked to the city in large crowds and packed Quần Ngựa stadium to watch the execution by guillotine.

In October, the nine remaining prisoners were executed at Bàng Garden in Nghĩa Đô near Bưởi Market. Their bodies were buried in a communal pit; their heads were taken elsewhere. This common grave was lost over time, but discovered again in 1998, and a memorial stele erected there.

While this poisoning attempt was not successful, it had great significance in the rising patriotic movement for national liberation.

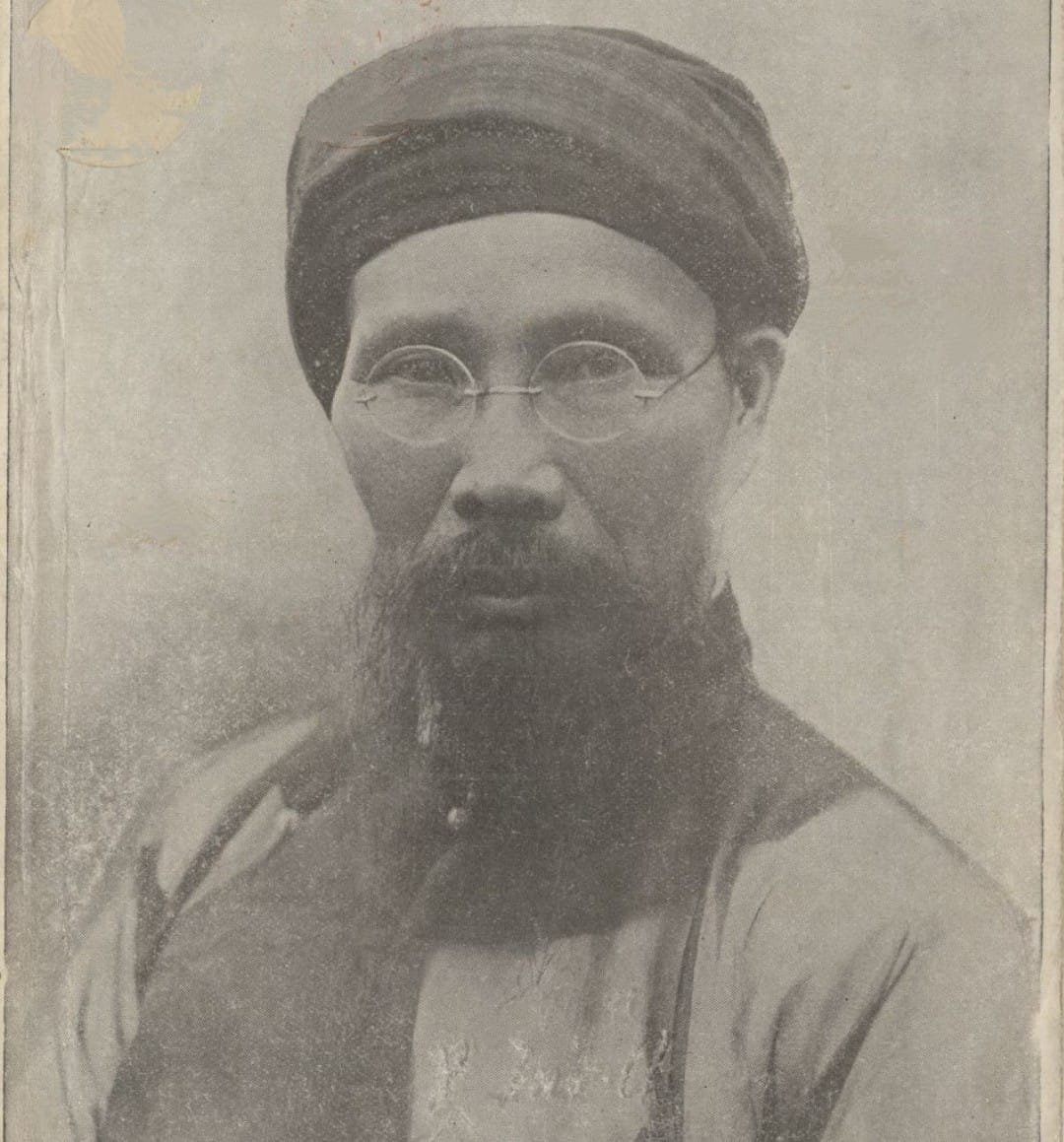

Before the Criminal Trial of Patriot Phan Bội Châu

Phan Bội Châu was a revolutionary with the aim of driving the French out and establishing a Vietnamese republic. He traveled abroad for decades, meeting with leaders in China, Japan, Thailand, and even Germany, to raise money for weapons and to send young people in the country to study abroad.

On June 30, 1925, Phan took a train to Shanghai. When he arrived at Beizhan Station, he was grabbed by secret agents, put in a car, and driven to the French Concession in Shanghai. The French considered his capture a stroke of good luck. He was taken and held in Hoa Lo Prison, and his criminal trial was five months later, on November 25, 1925.

That morning, the court was packed with people while the fog was still thick outside, with no room to squeeze through. At 7:45, he was led out of the prison; he wore a five-panel áo dài and a goatee, his eyes showing intelligence and courage. The people attending the trial in the courtroom stood aside respectfully, and he smiled and greeted them, representing the spirit of the nation. Two famous French lawyers were on hand to defend Phan without his request.

The judge read the 6-page indictment, accusing him of 8 crimes, any of which could result in a death sentence, considering him not a political prisoner but a murderer. Phan defended himself saying that from the start of his work to oppose the French government, he knew two things would be true: that Việt Nam would be free, and that he would lose his head.

Phan's lawyers argued that he should be released because he worked for the cause of bringing his people out of misery and poverty; the prosecution sought execution as a deterrent to others. When this was announced there was an angry commotion in the court. A fifty-year-old man in a turban approached the bench and offered to die in Mr. Phan's place; he had to be dragged out of the courtroom.

The final verdict was that Phan would be sentenced to a life of hard labor. The Vietnamese Youth Union sent 4,000 petitions: to every legislator in the French parliament and to every embassy in Paris or Viet Nam. College students and professors protested, and even the press turned against the French governor Alexandre Varenne. Varenne met with Phan's lawyers on December 7 and subsequently sent a request for amnesty to France. Phan was released two weeks later.

Varenne offered Phan Bội Châu one of two positions in his government: to be his personal advisor on Indochina, or to head the Ministry of Education. Phan refused both, only accepting a baton that Varenne gave him.

Perhaps he accepted it thinking of the Vietnamese parable: "The one with the stick will do the beating."

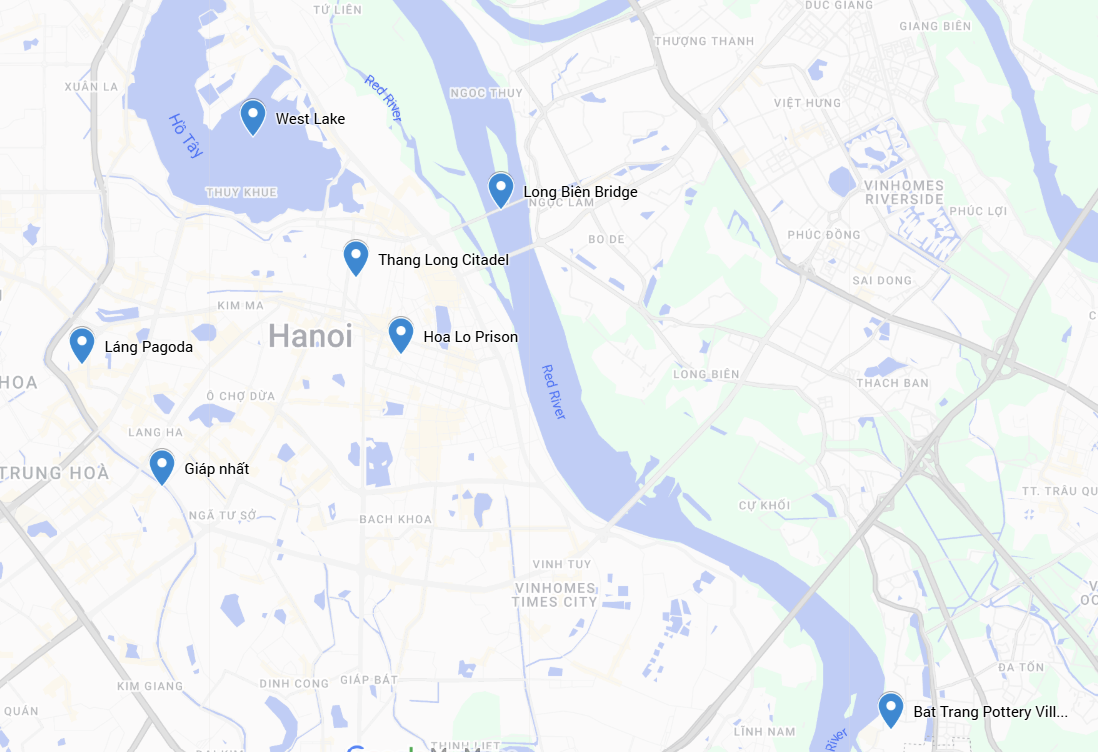

Mọc Village in the Suburbs

From Ngã Tư Sở, turn right on Láng Hạ street; follow the Tô Lịch river bank a little way and look across it to the Mọc area, and the communal house of Giáp Nhất village will soon emerge. Its three-door gate with tall and imposing pillars is adorned with the four sacred animals of Việt Nam: dragon, unicorn, turtle, and phoenix. The decorations also include yin-yang tiles, and likenesses of the Eight Immortals (of Chinese Taoism).

The temple was built on a mound surrounded by four ponds (two of which have since been filled in), which in feng shui is called elephant-shaped land. The main hall was built from bricks made at Bát Tràng (a world-famous pottery-making village) with lime and honey. The architecture lets in natural light, making it feel bright and airy inside. The temple worships the god Phùng Luông, a national hero who fought against the Tang army in the 8th century. The temple's inscriptions vow to burn incense to him for thousands of years.

For centuries, this has been an area full of culture and learning; many locals have passed the examinations to become national officials or famous authors, going back to the 16th century. The Mọc festival is famous throughout the area. It takes place once every five years, with the combined efforts of the five friendly villages of Mọc area.

There is a procession, and each village chooses men and women aged 19 to 20 to represent their village with uniforms of their particular colors and design. They hoist palanquins into the air, and there are dragon and lion dances to the music of drums and gongs and strings and flutes.

The procession of the palanquins 2025

The festival lasts at least five days and includes wrestling, cockfighting, rope climbing, hanging bridge walking, dice, human chess, đánh đu swinging, boxing, sword fighting, whip fighting, rowing, and blindfolded goat catching.

Even the most frugal people spend a lot at festivals, but they never regret it.

Mọc Festival

Entering the Spring of 1997, the people of the Mọc area held their festival again.

The festival held in 1934 in Giáp Nhất was legendary, lasting for half a month and bustling with people from sunrise to sunset. People still sing a folk song about that festival. But during the decades when Việt Nam faced nearly continuous warfare, the festival did not take place. Then peace was restored, but the communal house had been utterly destroyed by American bombs. In 1992, the five villages finally discussed reviving the festival, but couldn't yet raise the funds.

The processionists and palanquin bearers wear colorful costumes of many different styles. The palanquins are enclosed on three sides and contain the saints of each village. Pink and white horses and elephants were involved in the parades of old. The palanquins and other dancers move back and forth in a choreographed dance, and sometimes the palanquins are spun quickly

The palanquins arrive at Giáp Nhất communal house

When the procession reaches the host village, a ceremony takes place in front of the local communal house. Each palanquin is blessed by a priest, representing a blessing for the whole village.

Then everyone relaxes and starts drinking. There is Tổ Tôm Điếm, a traditional game with five teams bidding on colorful cards according to complex rules and with a host that sings in a traditional style. There is also walking on a suspension bridge over the pond, and circus and magic shows. Inside the communal house there is ca trù singing, outside there is chèo singing.

Tổ Tôm Điếm (aka "shrimp nest")

Fireworks shot up from the ground and shimmered in clusters that looked like purple and mustard flowers, emblazoned with the four Chinese characters meaning: "Peace under Heaven". Festivals are a form of culture imbued with the humanity of their nation. The joyful atmosphere is healthy and guides people to have a good heart.

Láng Festival

The village Láng used to hold a festival once every 10-12 years during droughts when rain was needed. The festival lasts for three days in March, and many tourists come to enjoy it. It is held every year now, but few know about the origins of the parade that started in 1936.

According to ancient lore, the village road was part of the rampart surrounding Thăng Long Citadel. King Trần Dục Tông (1341-1369) ordered land north of the Tô Lịch River reclaimed to grow onions and garlic, so it was called the Garlic Ward.

Vietnamese Human Chess

The upper village still has the remains of Nền Pagoda, built on the foundation of the home of Từ Vinh. According to legend, Từ Vinh held the position of General Inspector in the capital and was upright by nature. He saw that the marquis Diên Đình was using his status as the king's younger brother to commit many wrongdoings and tried to stop him. The marquis had a collaborator in the Zen master Lê Nghĩa known as Đại Điên (Crazy Đại) who used magic to kill Từ Vinh, cut him into three pieces and throw him into the Tô Lịch River. His body was recovered by three different villages, each of which built a temple to worship his moral qualities, and that is why it is said: "Mọc Village worships the head, Cầu Village worships the legs, and Pháp Vân worships the torso."

Từ Vinh's son Từ Đạo Hạnh was a highly learned Buddhist monk in his own right and became a national teacher during the Ly Dynasty (and the founder of water puppetry). He could not overcome his hatred. To avenge his father, he used supernatural powers to throw a Buddha statue into the Tô Lịch River. The Buddha's staff floated upstream. Đại Điên heard about this feat and went to Tây Dương bridge to see if it was true. There he was struck dead by that staff; the place where this happened is still called Ngõ Vụt (Hit Alley) today.

Years later, King Lý Nhân Tông was old but still had no son to succeed him, and neither did his brother the marquis Sùng Hiền, who went to a temple to pray for a child. Từ Đạo Hạnh entered a mountain cave and was reincarnated as the son of Sùng Hiền. This son was made the crown prince and would ascend the throne as Lý Thần Tông in 1128. He granted amnesty to prisoners, returned confiscated land, and rotated soldiers every six months - allowing them to return home to take care of their farming duties every year.

In the early 12th Century, Láng Pagoda was built to worship Từ Đạo Hạnh. Every year the villagers have a festival and repaint the palanquin and all the statues. The chosen palanquin bearers must sew their own clothes and practice the palanquin movements every week. The biggest festival was in 1936.

At 6am, the procession solemnly begins. The processionists wear blue robes and hold staffs, swords, five element flags, and pink and purple fans. They take one step at a time and then stop. More and more people gather to watch them. Four bare-chested men carry the altar with an incense bowl, a golden tree made of gilded paper, and four statues at the corners. The statues represent the four villages protected by "the heavenly king". Inside the palanquin is a statue of Từ Đạo Hạnh, but it is covered by a fan so few can see it.

At about 7:30am, the palanquin arrives at the riverbank. A clay firecracker nearly as tall as a bamboo shoot is set off; there are many holes and layers of it, some that spin around in different directions like pinwheels. The palanquin is then lowered into the river. The bearers carry the palanquin across the river in waist-deep water. Local custom states that the two riverbanks here are two dragon jaws, so crossing here will lead to a year of prosperity.

Probably for the best: these days they erect a temporary bridge across the river.

The procession eventually arrives at Duệ Pagoda, a place for worship of Đại Điên. Drums and gongs sound, and then fireworks streak toward the pagoda like cannonballs. A firework bursts on the pagoda, damaging its tiles. More fireworks fly out from the pagoda grounds out above the processionists. It is a metaphorical recreation of the battle between these two Buddhist rivals. The nuns pray for peace from a nearby field.

Finally, the processionists leave with jubilant faces, as if they have won the battle.

(Đại Điên still seems like an unlikely Zen Buddhist to me.)

Đánh đu swinging

Over the following ten days, the festivities continue day and night with wrestling, boxing, đánh đu swinging, sword fighting, cockfighting, small bird fighting, flag swimming, and gambling with cards or dice. In the evening, oil lamps and bamboo lamps are lit up everywhere and there is chèo and chầu văn singing. Anyone who has been to the festival will never forget it.

Chèo singing

Western Festival

The Western Festival was introduced at the end of the 19th century to celebrate Bastille Day. Later there was another festival called "Armistice" to celebrate the French victory in 1918.

In Hà Nội, there was an annual military parade: mounted cavalry looking majestic, military bands with drums and bugles, convoys of armored vehicles and artillery. The navy, army, and air force all participated with tidy uniforms in different colors. Dozens of planes in three rows roared by with power. Twenty-one cannon shots were fired. Spectators pack both sides of the street. Various kinds of entertainment were organized; some bring tears to our eyes now and have since been condemned by public opinion.

A sack race, where people must race with their feet in a sack that is drawn up to their armpits. The contestants were mainly poor people hoping to win a prize. When the whistle blows to start the race, many of the runners tripped and fell immediately taking some of their competitors with them. Those who shuffled their feet could win even though they went very slowly.

Running while holding a plastic ball in a wooden spoon. Five competitors lined up, but four dropped the ball immediately; only the smartest contestant walked steadily to win and keep the ball from falling.

Climbing a greased pole much taller than a lamp post. At the top is a hoop where several prizes hang: an umbrella, a turban, a pair of shoes, a bottle of Western wine, and a box of biscuits. Whoever can climb to the top can claim one prize. Most could climb and climb and tire themselves out only getting halfway up. The poet Nguyễn Khuyến wrote it's "as much fun as it is humiliating!"

Licking a pan: the pan is black with soot and inside is a flat coin worth 20 cents. You can only push the coin with your tongue to the edge and over the lip of the pan where it usually falls back down. The competitors have trouble breathing and come away with horribly dirty faces.

There are bicycle races, foot races, and occasionally car races. The sports cars have only one seat in the middle of a short, diamond-shaped chassis. The roads are too narrow for more than one to go at a time, so the competitors race one at a time, doing ten laps while a referee times them with a stopwatch.

Turtle Tower and the treetops around Hoàn Kiếm lake are lit up with colored lights at night, while round lanterns float on the lake's surface, half submerged. When the wind blows, the lanterns drift to a corner of the lake.

On the dike near the Clock Tower there were outdoor movie screenings at night. They were silent pictures, and the screen could be viewed from both sides.

During World War II, the festival was suspended. When they returned, they were held less regularly. The last festival was held on July 14, 1954. Even though France had been defeated at Điện Biên Phủ, they still held the festival and parade to show off their military might. Paratroopers jumped from overhead, landing in the lake where men in canoes waited to pick them up.

Nowadays, talking about this Western Festival is like mentioning the ghost of colonialism that has been buried in the dust.

In the next edition: A tour of the landmarks of the city