Readings: Hà Nội in the Old Days, Pt. 1

The library of my rural school is small and quiet. The librarian laments that students don't come to check out books anymore because - whether for recreation or for class - they only read books online. I see an interesting Vietnamese book with short chapters and ask if I can check books out. She is happy to let me and I am soon signing my name in her paper ledger.

Reading this book through a slow process of translation, it occurs to me that many Vietnamese books - like this one - are not available in English translation. The following series of posts will not be translations of books, but a chapter-by-chapter summary of their contents. It should be read with the caveat that I may not always fully understand the meaning of passages, especially when the writing is at its most poetic. The books will help me understand the local perspective on their own culture and history, and I hope to pass that perspective on to anyone else who is interested in it or spur interest in these writings abroad for a proper translation.

Gunfire at 10:00 AM

"80 years ago" residents of Hà Nội - and even people out in its suburbs - heard gunfire at 10:00 AM. Outside Cửa Đông (East Gate), soldiers hauled a horse-drawn cannon out and fired a round that shook the earth and sky. It was a flare. They did this every morning. But the ordinance costs were expensive, so the government ended it after 1931.

The author still feels like he can remember this sound....

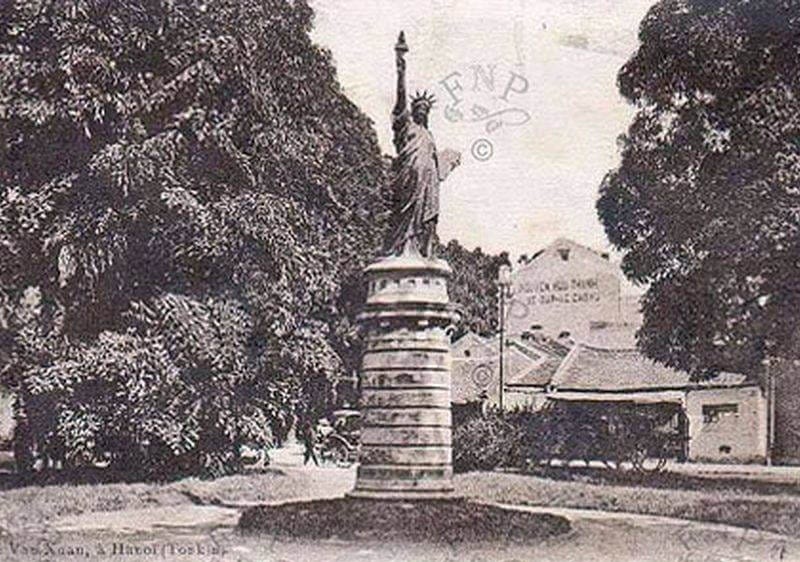

The Statue of Bà Đầm Xòe in Cửa Nam Flower Garden

In the 19th Century, in Cửa Nam flower garden, there was erected a statue of Lady Liberty, and the residents of Hà Nội came to call her Bà Đầm Xòe "Flared Madame" (because of her 'flared' flowing dress style). She was a replica of the one in New York, scaled down to 7 meters tall including her cement pedestal.

When the Japanese overthrew the French government in March 1945, the mayor Dr. Trần Văn Lai changed all the street names of French origin. The only French statue that was allowed to remain was one of Louis Pasteur in the Pasteur Garden, because of the doctor's admiration of his significant contributions to humanity in the field of medicine.

Lady Liberty - despite not having "the blood of colonialism" - was also removed.

Some Features of Old Life

A description of Hà Nội circa 1900 is provided, based on a book by Robert Dubois. Hà Nội province encompasses the same 10 districts as it does today, with 600,000 residents, 100,000 in the city itself. It is the most crowded area in North Việt Nam. People have to haggle for good prices, and the shopkeepers complain of high overhead. Most of the shopkeepers are women; many breastfeed while working. A major train line is constructed shortly after 1900 connecting Hà Nội to the rest of the country, and many big ships sail the Red River. Hopes for the economic future of the city are high.

A philharmonic concert hall opens on Hoàn Kiếm Lake in 1899, and both French and Vietnamese luminaries attend on opening night. The concert hall would later be torn down and the Thăng Long Puppet Theatre erected in its place. In northwest Hà Nội a magnificent horse racing track is erected and attracts anyone with a passion for horses; this would later become the site of a sports academy.

West Lake - A Source of Inspiration

The poet Cao Bá Quát wrote several poems about the beauty of the landscape around the West Lake. In one, he likens the grass-covered gentle hills of Tây Hồ to the curves of the body of Tây Thi - one of the four "Great Beauties" of China. The name of the lake was given in 1573. In the winter morning, fog lies over the lake and it appears as if in watercolor. Willows droop into the water along Thanh Niên street (the famous street that separates the West Lake from Trúc Bạch Lake).

At the end of a long peninsula is Phủ hamlet where people worship Princess Liễu Hạnh, the mother goddess. On another peninsula, Kim Liên Pagoda still stands, and you can hear its Trấn Võ bell reverberate in the morning recalling the sounds of ancient times.

Two hundred years ago, on the night of the Mid-Autumn Festival, Lord Trịnh Sâm enjoyed a leisurely trip around the lake in a dragon boat with his lady, lit by lanterns, while palace maids sung softly to the accompaniment of a guitar. Standing at the front of the boat, the pacified lord raised his glass of Portuguese wine and declared peace: he will let the Nguyễn family hiding in the South remain there, knowing their throne will fall to him eventually.

In the poem "Lady Tây Hồ Chanting" by Nguyễn Huy Lượng (1801), Tây Hồ adorns herself with fresh grass, green shadows, and purple waters like makeup to always be beautiful for people. The famous 19th century poet Bà Huyện Thanh Quan was born in Tây Hồ, and its memory haunted her such that the 'greasy grasses' of Trấn Bắc palace filled her with disappointment.

Bích Câu Temple

This Taoist temple was renowned for its scenery, and being garlanded with flowers or other colorful plants, according to the season. It was located on Kim Quy "mound" near An Trạch village and was surrounded by the blue waters of Cánh Phượng lake.

Legend has it that during the reign of Lê Thánh Tông (1400-1497), there was a handsome poet-scholar named Trần Tú Uyên who liked to travel. On a cool spring day he goes to visit Ngọc Hồ Pagoda (a Buddhist temple still extant next to the Temple of Literature) and sees a beautiful girl. They stop to look at each other. He says hello, but she just smiles. He follows her, but she suddenly vanishes. At night, he tosses and turns, until finally dreaming that he will find her again at Cầu Đông market. The next morning, he races to the market and searches high and low but can't find her. He is about to leave when he meets an old man with a white beard selling paintings, and there he sees her likeness in a painting. He buys the painting and takes it home.

One day he returns home from school to find rice and soup already prepared for him. The next day after leaving for school, he has a sudden thought to turn around and go back and when he walks into his home he sees her there preparing rice. She tells him she is the fairy Giáng Kiều and they are destined to be married. They get married and have a passionate love affair.

When summer comes and the fruit sweetens in his garden, Tú Uyên starts to indulge in alcohol. Giáng Kiều admonishes him but he doesn't change, so she leaves angrily for the fairy world. Tú Uyên is shocked and full of regret. He turns to martial arts and the teachings of Lao Tzu to improve his morality and cultivate himself. After many years, he attains enlightenment and Giáng Kiều suddenly appears again. They live happily together in harmony and she bears him a son named Chân Nhi. One day a pair of white cranes lands in their yard, and the happy family rides away on the cranes to live in the fairy world.

Bích Câu Temple is dedicated to Tú Uyên and is considered the starting place of Taoism in Vietnamese religion. A variation of Taoism mixed with Zen Buddhism that emphasizes faithful human love alongside harmony with nature, rejection of fame and fortune, and adherence to strict morals. The immortal Trần Tú Uyên is worshipped at this temple, particularly by writers and poets. A poetry club organizes public readings every month.

A festival at Bích Câu Temple in the news. (Use Youtube's CC options for translation.)

Most of the temple's ancient features as described no longer exist. The lake has been filled in, the mound flattened. The French burned the temple down in 1946. The people donated to rebuild it in 1951-1953. Ca trù performances (a traditional music style of storytelling singing) are given for free every week.

Ca trù singing

Seven Bridges Across Tô Lịch River

Tô Lịch River was given its name in 545; it is a tributary of the Red River. It has a gentle, lyrical look and has never caused any floods. Seven bridges were erected by Nguyễn Hữu Thiêm in the 1700s. He was paid two buckets of silver, and a bag of betel nuts. They were originally built in wood or brick.

Mọc Bridge featured in several important military victories. In the 1400s, Ming Dynasty troops tried to attack Vietnamese forces by crossing it, but they were discovered and ambushed. In 1789, Vietnamese troops crossed it in a sneak attack on the Thăng Long Citadel, purging the country of Qing Dynasty invaders.

In 1947, Vietnamese troops demolished the Mọc Bridge during a retreat to slow French forces. Now a plain bridge built of reinforced concrete stands there.

Bullet Wound in Cửa Bắc Gate

There are two large cannonball holes still visible today in Cửa Bắc gate.

In 1882, the newspaper announced that French forces were preparing to enter the city. Everyone was scared but too stubborn to leave. The French gave mayor Hoàng Diệu an ultimatum to surrender by 8:00am. He tried to ask for an extra day, but the French opened fire at 8:05 AM. Cannon fire exploded a gunpowder warehouse. Hoàng Diệu led the battle from the back of an elephant.

When the French poured over the walls of Thăng Long Citadel using ladders and it was clear the battle was over, the mayor got off his elephant, bowed to his court, and left the battle on foot. He killed himself with his belt under the banyan tree at Võ Miếu Shrine.

Everyone was very sad that the city had fallen and grateful for Hoàng Diệu's actions. The casualties on the Vietnamese side were 40 dead, 20 wounded. The French lost 4 soldiers, and 1 officer was wounded.

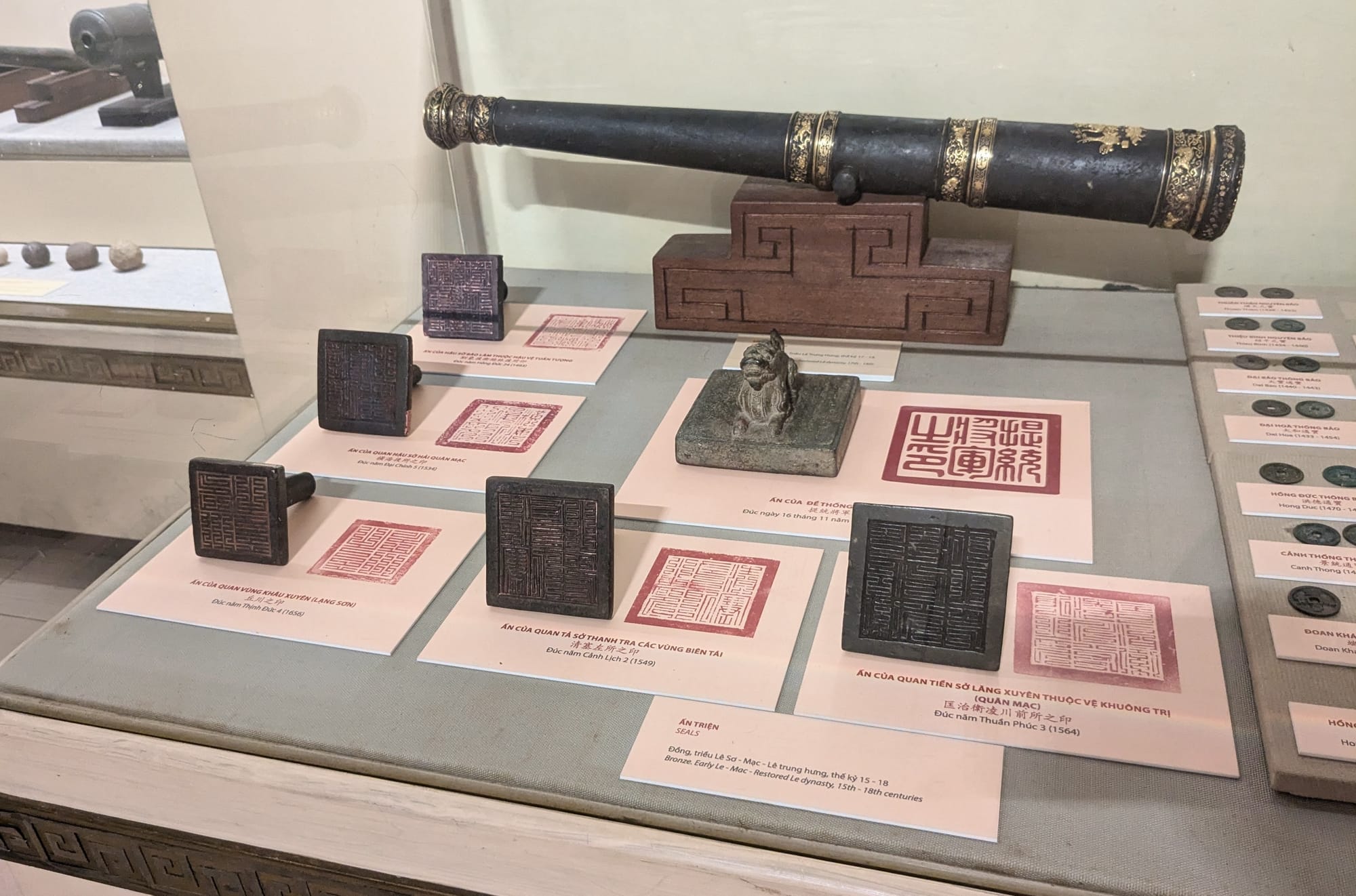

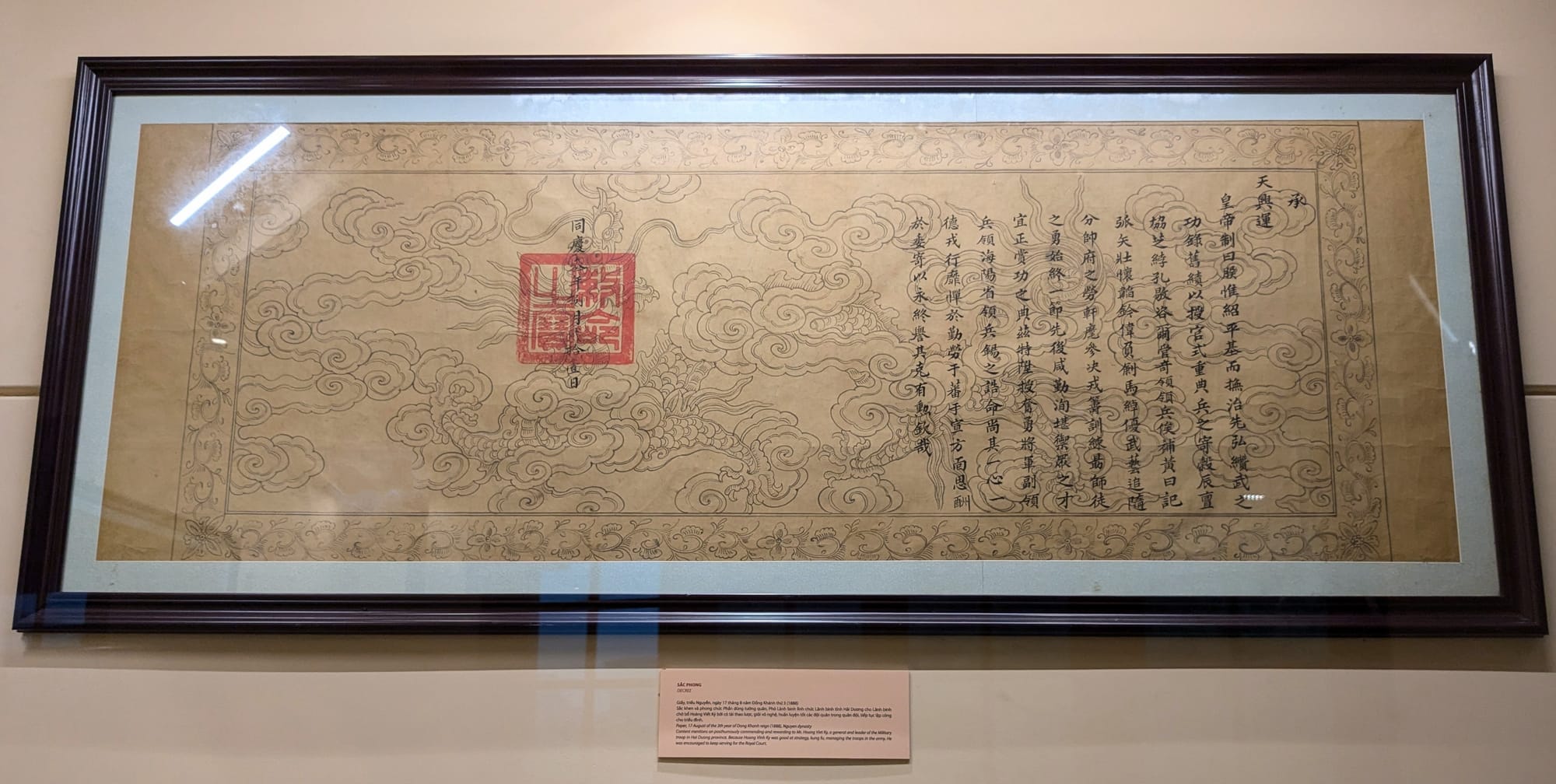

The Event Where "The Kingdom of Việt Nam" Was Destroyed

As a small nation next to a giant, Việt Nam has always needed to pay tribute to China. Even immediately after winning wars, they paid tribute in order to have lasting peace. In 1804, during the rule of Gia Long, the Qing emperor presented him with a seal made of silver - half of the seal was in Chinese, the other half Vietnamese. This was the seal of the "The Kingdom of Việt Nam". From then on, Việt Nam was afforded special status. The seal was guarded carefully and only used in correspondence with the Qing court in China.

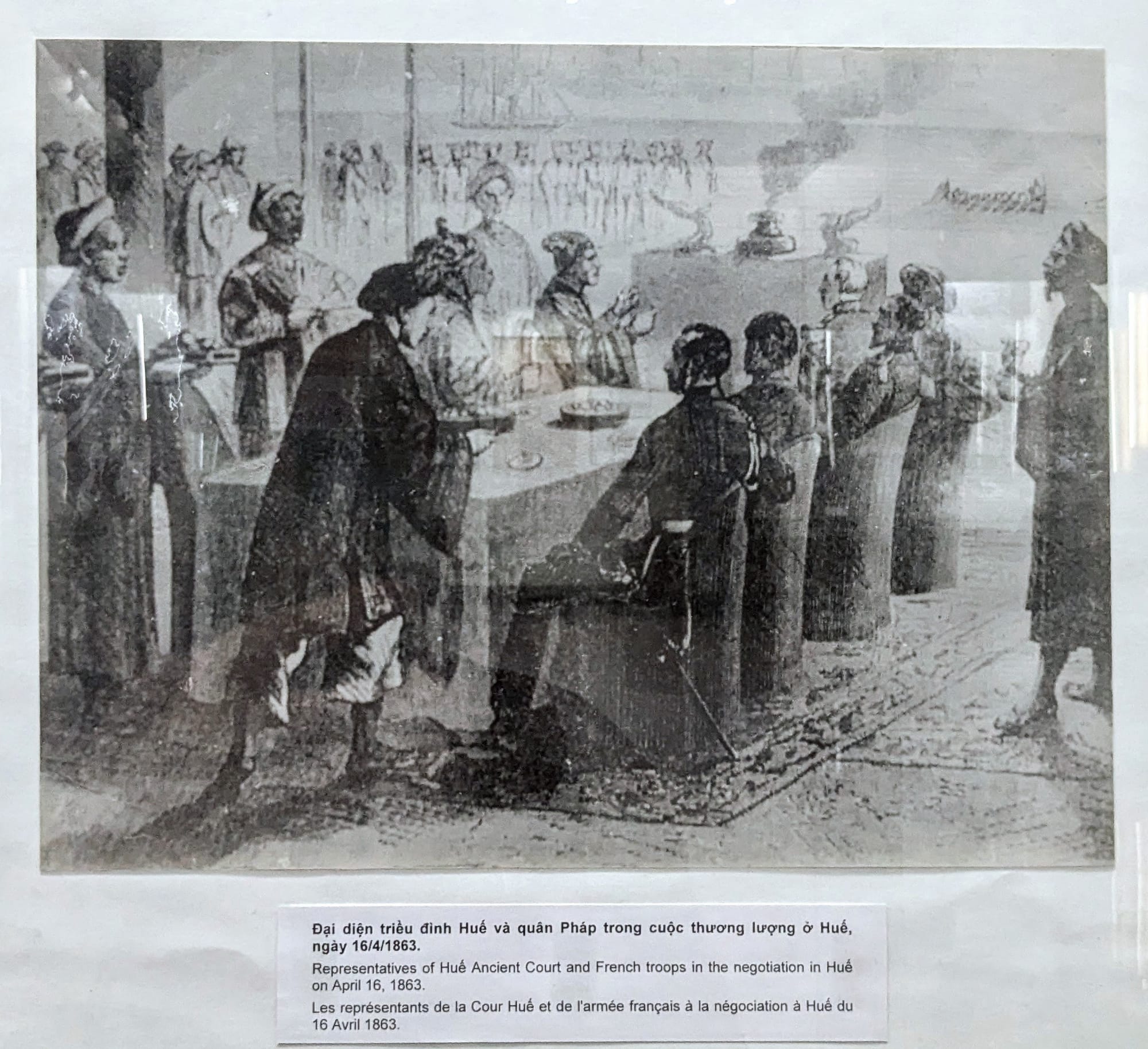

In 1859, French gunfire first fell on Việt Nam in Đà Nẵng. In 1862, a Peace Treaty was signed and the South ceded 3 provinces to the French. King Tự Đức tried to redeem it since one of the provinces lost was where he had been born. He sent a large envoy to Paris. Emperor Napoleon III was on vacation and the envoy waited for a whole month for an audience. When Napoleon heard their pleas he almost conceded, wanting only that the French retain Saigon, access to the Mekong River, and to receive an annual tax. But Napoleon's naval minister did not agree so the treaty was never signed. For 25 years, there was fighting from the South to the North. The King in Huế finally surrendered.

The French then declared that Việt Nam would no longer be dependent on China and ordered the seal turned over to them. The Huế court was shocked. How did they know about the seal? The French had an interpreter who knew Chinese well; he had seen its imprint on a scroll and surmised its meaning.

The Vietnamese refused to give the seal up but could find no way to smuggle it back to China where it was cast. In compromise, they proposed to have the seal melted down and cast into a new seal.

Thus, the Vietnamese court of Huế presented the seal in a ceremony - where it was examined for authenticity and then melted down - right there in the lobby of the French embassy. That was the moment the relationship with the Qing Dynasty was destroyed.

In the next edition: Ceremonies, Festivals and a Trial