Living in Việt Nam, Pt. 7 - Of Mice and Nem

"He shall know your ways as if born to them." - Frank Herbert, Dune

"What the heck is going on??" - Chris in Việt Nam, often

March 2025

My bicycle arrives in a surprisingly light box; like all deliveries it comes on the back of a motorbike. One of the school's guards offers to help put it together, and I'm a little shocked when he delivers it a couple hours later. It is very lightweight but seems like it will do. I soon learn that the biggest downside to its cheapness is that it has no shock absorption and a hard seat. I feel every bump in the country roads of Việt Nam.

As I'm looking it over, several other people come over to inspect it with me. One of them asks me how much it cost; they always do. When I tell them "two million" (~$75), one of them snickers and mutters something to the others. Everyone laughs, and then they remind me the Peace Corps gave me three million Đồng to buy it. It's true; I forgot I told them that, when my principal offered to help me buy a used one locally. I try to tell them that I need to buy some accessories too and I won't get more money if I need sửa chữa (repairs). They just smile and say 'okay'; there's a hint of admiration in their smiles.

I ride for as long as an hour at least four times a week. Sometimes, I pick a nearby village on the map and set out with this destination in mind. When I come to a village I've never been to before, I turn a lot of heads! A few will stare with a frown or neutral look, most look at me with shock and then a confused smile. Especially after I wave and say in a sing-song voice: "Xin chào!"

Sometimes I hear them say, "Tây!" For an embarrassingly long time, I think they're saying "Thầy" (teacher) because I can't hear the tones or the difference between 't' and 'th', and because I'm addressed that way a few dozen times a day by students. Then one day, seeing my friend Sean for the first time in a few months, comparing notes about our experiences, he casually mentions: "Hey, do people shout 'westerner' a lot when they see you?" I connect the dots immediately and bring my palm to my face. It's not like I didn't know that word. We lived in Tây Hồ (West Lake) for three months.

It never feels malicious, only an expression of amazement or to let others nearby know: "Hey, there's a Westerner! Don't see that every day!" So now I just respond with my new catch-phrase - "Đúng rồi!" (Correct!) - to more surprise and usually laughter. And if I'm wrong and they are saying "teacher", it still makes sense.

In March, there are about three weeks where the humidity is off the charts. My air purifier's sensor remains continuously at 90%, which I surmise is the limit it can measure and the humidity is actually even higher.

For weeks, the school's janitor has fussed at me about keeping my window and door open in the evenings - antithetical to my A/C lifestyle - but in the humid weeks it becomes clear why. If you don't keep the air moving, mold starts to grow quickly. I have a full mosquito net screen door on my front door, and mosquito netting on the window next to my kitchen; it is straight through for a breeze to keep the airflow going. My ceiling fan and floor fan assist when that's not enough. Volunteers in other living environments reported mold growing on backpacks, leather belts, and books. I'm lucky to escape the worst of this, only having some papers and books get soggy from the air and get warped, permanently curled at the corners.

One day, I hear some scratching sounds in my room. Whenever I move around slightly or turn on the lights, it stops so I can't quite pinpoint where it is but it's clear I have a mouse or a rat. I thought I had sealed up all of my food, but the next morning I realize I left some fruit on top of my small fridge; it's partly eaten. I have English Club that day, so I don't have time to go to war against the rodent, so I take out my trash and seal all of the food up. That night I catch a glimpse of my roommate by flashlight; it has grown bolder and louder. I try to scare it away, but I don't have a way to catch it so I wait until the next day.

The next morning I find a new mess, as some papers that had been left on my living room table have been completely shredded and left in a pile. I assume there is a nest under my bed, where I had been storing flattened boxes for most of my appliances in case I needed to return anything. I put on gloves and start pulling everything out. I pull my suitcases out and leave them outside to inspect and clean later and throw most everything else away.

The janitor asks what I'm doing; I tell her "Chuột" (mouse) and she just laughs. She ends up taking my large boxes to tear down and use as mats for the students to wipe their boots of mud on rainy days. I find the rat still in its nest in the tote bags I had stuffed into my luggage after moving in. When it escapes and scurries across the courtyard towards two female teachers, they boldly run after it trying to stamp it dead with their sensibly flat-soled shoes.

One day in the afternoon, one of the women on the school staff knocks on my door. Like most of the teachers, she is a little older than me, so I address her as chị (older sister). Chị speaks a little English and instructs me: "Come to the garden."

Across the road from the school is a ditch filled with water; a bridge crosses the water to the school's football (soccer) stadium. But around the edges, and in between everything - seemingly everywhere - is room for growing plants for food. The school lets the staff grow vegetables there.

I teach chị the idiom "green thumb" and explain that I don't have one, as much as I'd like to. I am told that if I want to grow anything, I just need to buy the seeds and they will plant it for me. I help her water the plants by lowering a watering pail on a rope into the ditch and hoisting it back up.

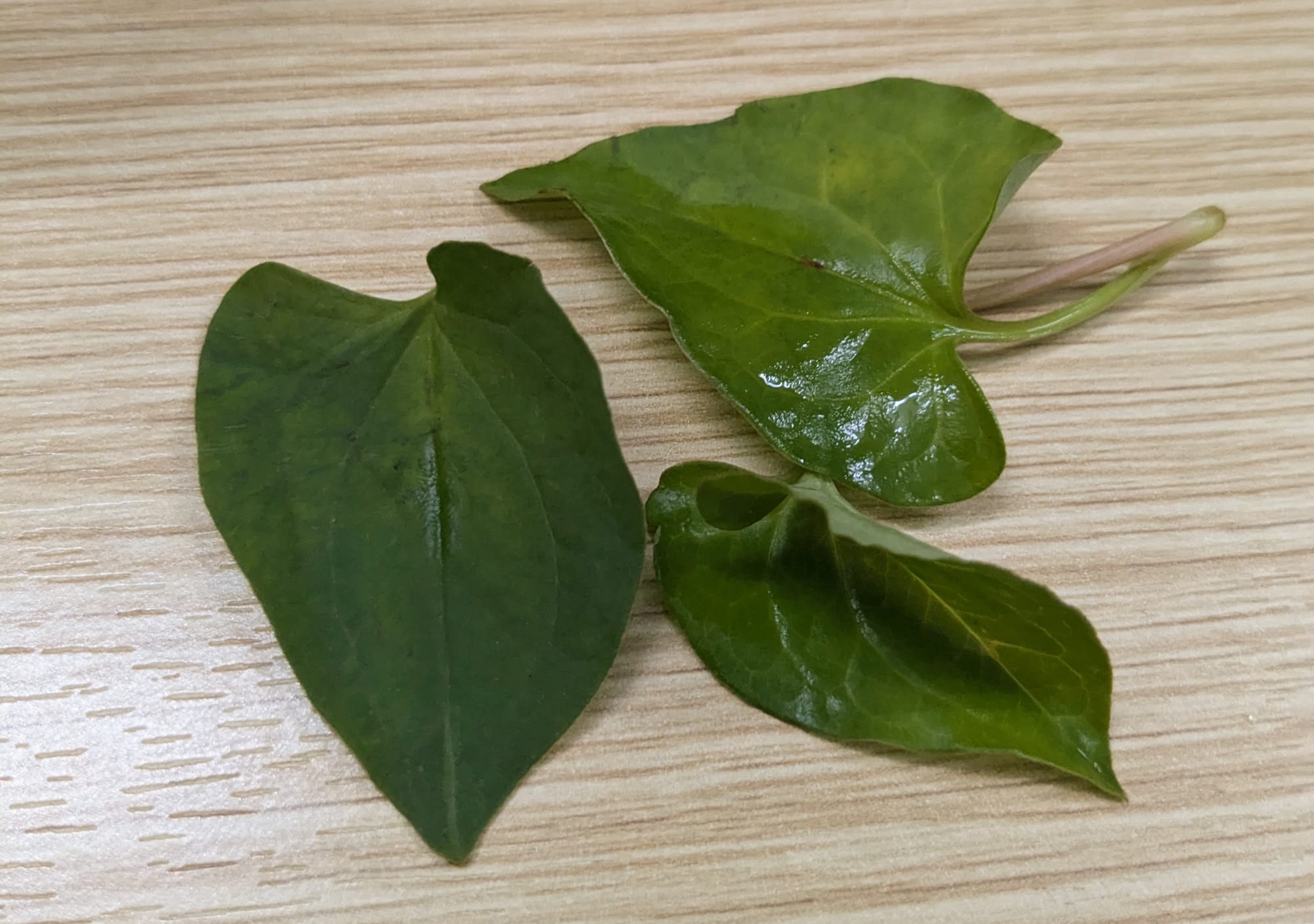

I am not familiar with most of the kinds of rau that are grown in northern Việt Nam. Rau (pronounced 'zow') means vegetables broadly but mostly the leafy greens. Chị tells me that Vietnamese name a lot of plants after things that they look like. She points to one: "That's rau chân vịt. Do you know it?" "Duck feet?" She laughs. I don't see the supposed resemblance.

We come to rau mùi, I know this one already: "aroma vegetable" is cilantro. Chị tells me I can come here and pick some whenever I want. (Jackpot, I think to myself. I love cilantro.) The plants are so young that the leaves haven't grown round, and I don't recognize them at first. But I recognize the smell.

Cooking that night, I soon learn that the flavor of young cilantro is so much stronger than I'm used to that it tests the limits of my love for cilantro.

I thought Việt Nam would be a paradise of topping my food with handfuls of fresh herbs, envisioning handfuls of mint, cilantro and basil on every dish. But in my village, it's mostly just mint. They also use rau răm (Vietnamese coriander) in soups, and unfortunately that tastes like soap to me, much like regular cilantro does to some people.

And sometimes they use rau diếp cá (fish mint) in the herbs served with grilled meats. To me, this herb tastes like pennies and smells like a dog that ran around in the rain. (I text Thùy this and she laughs, saying not all Vietnamese like it either.)

I am occasionally invited over to people's homes, and one day a teacher invites me over to cook nem at her home. More formally known as nem rán they are the Vietnamese equivalent to fried egg rolls, using rice paper which makes for a thin and more fragile exterior but one that is wonderfully crispy.

The boundary between indoors and outdoors is more fluid in the typical Vietnamese house than I am used to, and kitchens sometimes feel like they are more outdoors than in. Here we squatted down to wash and then cut our vegetables on the concrete floor over the large plastic tubs essential in a Vietnamese home for all cleanings tasks. After watching me struggle, I am offered a low stool to sit on; I don't know how the Vietnamese can stay squatted and work for so long, but they have a way of balancing that puts no strain on their knees or ankles.

I am accustomed to making fresh spring rolls at home, so my rolling skills are not too shabby, and I am surprised to find that it's not even necessary to do a tucking fold at the ends: just do a long tube and then chop them into smaller pieces after frying. Paired with a slightly sweet, watered-down fish sauce for dipping, these homemade nem were the best I have had in Việt Nam, much better than the restaurants in the city.

Everyone in the village always asks if the weather in Việt Nam is okay, like they're worried it will kill me or drive me to quit. But it has been much more moderate than I expected. In fact, I learn a large-scale weather system has actually made the entire season cooler than normal. A refreshing breeze blows most nights, so after cycling and showering, I cook dinner with my front door and back window open to let a nice cross-breeze in my room.

Through the mosquito net I hear the tell-tale shuffle of hard-soled slip-on sandals on the courtyard tiles outside. It's "Chú", one of the school's guards who is an "uncle" to me in terms of age. I slip through the strip of magnets keeping my door netting tight to say hi, because I know he is coming to see how I'm doing; I have already turned the lights in my building on the way they like it at night.

"Chào chú!"

"Nước," he replies, raising an imaginary cup to his mouth. His white undershirt is bunched up under his armpits, leaving his belly exposed to feel the cool, fresh air.

I join him in front of the guard shack for strong green tea. Chú is watching the finals of the ASEAN Cup on his phone; Việt Nam will end up winning against Thailand.

Across Southeast Asia, there is controversy about letting foreigners play on their national teams. But chú, and most Vietnamese that I have talked to, are very proud of Nguyễn Xuân Son, a Brazilian-born footballer (also known as Rafaelson) who has lived in Việt Nam for the five years required to become a naturalized citizen. I am frequently shown videos of Xuân Son being spotted out-and-about in Hà Nội, doing such quintessentially Vietnamese things as having his entire family on his motorbike with him - two kids sandwiched between their two parents - and stopping to buy bánh chuối from a street vendor (fried banana).

We are soon joined by another chị, a staff member who sometimes spends the night at the school. Up until a few years ago there were rooms for teachers to spend the night at the school; many commute as far as an hour to their home. The school needed the space for more classrooms, so now teachers often put four chairs together in the teachers' meeting room to take a nap on after lunch. But a few staff members have cots tucked away in a corner of their office, as a matter of convenience.

"Ăn cơm chưa?" chị asks. The most common of greetings between colleagues here: "Have you eaten?"

This is a good time for me to practice my Vietnamese which occurs a few times a week. She is good at asking me simple questions so that I can understand. She asks how often I call my parents, and whether I am sad. At first, she asked a lot of survival questions: "Can you eat the food here? Do you get enough vegetables? Are things suitable for you?"

But now she has moved on to which dishes I like the most, now that she knows that I seem to like just about everything.

She smiles as she tells chú the new thing she learned about me today: "Chris likes bún đậu mắm tôm!"

Chú is amazed. Foreigners don't usually like it. He vows that next week the three of us will make it and eat it together. I tell him that will make me very happy, and he smiles content.

To be clear, the first time I tried bún đậu mắm tôm I actually didn't like it at all. My Vietnamese teacher Thùy had taken me to a small quán ăn, a casual type of restaurant usually in the front room of someone's home, to try it. I had eaten and liked everything else she had gotten me to try.

This would be the "final boss" of Vietnamese food, my ultimate test.

Bún đậu mắm tôm is sort of a strange dish, seeming more like a Vietnamese version of fast-food. A light meal more suitable for sharing with friends than dining alone. A meal suitable for soaking up alcohol, but for some reason just as likely to be eaten for breakfast or lunch than late at night.

In this dish, the noodles (bún) are drained and allowed to stick together in big clumps - these clumps are then cut into bite-sized pieces with a pair of scissors. Everything else on the plate is also bite-sized, herbs, veggies, sausages, and crispy fried tofu (đậu). And this is all prepared to go into the star of the show: the dipping sauce.

Mắm tôm is a fermented shrimp paste with the strong odor and the unpleasant pinkish grey hue of something that's been left out for too long. It tastes just as strongly, although when used as a dipping sauce it should be augmented with finely chopped chilis and a generous splash of lime and/or kumquat juice to add some sourness and sweetness.

I've come to... appreciate... the complex umami flavor that the shrimp paste brings to the somewhat bland flavors of bún đậu, but the first time a foreigner tries it the closest smell/taste association your mind can connect it to - like durian fruit - is rotting garbage.

While others at the table took one whiff or one taste and "noped" out, I sat at the table pensively eating bite after bite, chewing slowly, searching my tastebuds for something pleasant.

"I don't think you like it." Thùy observed.

"No...... I don't think I like it even a little bit...." I admitted.

"Then I'm sorry, but I can't give you full citizenship of Việt Nam..."

A few weeks later, I am sitting in my room at 9:30am after having a couple of early classes, when there's a knock on the door.

"Chris! Come here!" Chị says.

I follow her upstairs to a door I've never been in. Inside is a narrow storage closet sized room with floor-to-ceiling shelving. In the middle a narrow desk has been placed against one wall. Five people are crammed into what little space is left around the table.

The table has two platters of heaps of herbs, bún and đậu. I want to ask if this is a secret, illicit bún đậu mắm tôm party. A bún đậu mắm tôm speakeasy.

Chị points to my skin and says "đen" (black). I have been cycling so much that my skin has gotten drastically darker. She puts her arm next to mine and points out that they are now about the same tone.

I smile, and don't know what to say, so I decide to make a little joke. I say "Yes, but..." and I pull up my sleeve a little, showing the bright white skin of my upper arm. Everyone laughs.

We sit in this little room eating with the door open to get some of the fresh morning air, laughing. Even though I don't know what they're saying, I briefly feel a sense of community with them that I hadn't yet experienced in this country.