Living in Việt Nam, Pt. 4 - Pomp in Circumstances

Note: For many reasons, I will not identify the village or school where I am living, primarily out of respect for the people I am here to serve. I will not use the real names of people and may purposefully obscure identities in my storytelling. I don't think anything I have written reflects poorly on anyone at my site, but nevertheless: please keep in mind that the following doesn't represent fact or truth, only my opinions and limited point-of-view.

Pre-Service Training Week 6 - November 2024

On Monday, we meet our "counterparts" from our future high schools in the ballroom of Thă'ng Lợi Hotel. The hotel was built by Cuba in the 1970s and exudes modernism in a tropical setting. The hotel's rooms are even built on a peer jutting out over Hà Nội's West Lake. It is where we spent our first few nights in Hà Nội, and now we have returned. We nervously greet our new colleagues, trying to use the little Vietnamese we have learned so far, pronouncing the words poorly.

Counterparts are the people at our high schools we will talk to the most often, who will help us adjust to living in our communities and make sure we have what we need. Most are the English teachers we will work with directly and some are the heads of our departments who will make our schedules. The teachers know English grammar better than we do and can quickly recite even the least used rules of our language. But few have held a conversation in English in years, or sometimes decades.

For a day and a half, we attend classes and team-building exercises together. Thă'ng Lợi sets elaborate Vietnamese family-style meals for us. We try to show that we already know how to eat like a local: squeezing fresh lime over small dipping plates of salt and sliced red chili peppers, using our chopsticks confidently to pick up chunks of plain, boiled chicken and tap them to the mixture for flavoring.

The Vietnamese Peace Corps staff try to emphasize the policies and teaching techniques that will be the most effective in this country's typical classroom. We are supposed to be co-teachers only, tools to enhance the classroom by giving the teachers a native speaker with natural pronunciation. We also go over rules and regulations. ("Peace Corps Volunteers are allowed to drink alcohol. But they are not allowed to get drunk.")

At the end of the seminar, the principal of one of the schools is invited up to the stage. Like most of the principals, he knows little English and hasn't spoken much for two days. But he has asked if he can sing us a song - karaoke is often a part of the end of collaborative meetings here - and he sings a love song a cappella in perfect-sounding English.

After lunch on the second day, we take taxis with our counterparts to visit our "future sites" for the first time. The Peace Corps does this all over the world early on in the training process to better prepare the volunteer. The ride to my site is long, and an awkward silence occasionally sets in as we drive through paddy fields of rice and lotus plants for two hours.

My counterpart loves to read the news every day and he congratulates me for the election of President Chump (his pronunciation, not mine). Most Vietnamese don't seem to realize that Trump might be a controversial figure in America; I don't think it comes up in their news at all. They mainly appreciate that he will be tough on China and that high tariffs will be a boon for Vietnamese trade. I tactfully keep my opinions to myself.

We get to the school around 2:00 PM. The guards open the school gates for our car, which takes us straight to the central building. All the students are in classes which ring the central courtyard. I am quickly ushered into the principal's office on the second floor and hot green tea is served. My counterpart translates as I meet my principal. He doesn't speak English, but he has practiced a few words to say to me. He has a genuine, warm smile and I feel very welcomed that he took the time to make this gesture for me.

After only a few minutes, I am told that we must now go to the police station. We are all driven there, even though it is just around the corner. I was expecting this, and I have my passport and visa on me, so that I can register with the police. It is standard practice anywhere you go as a foreigner in Việt Nam; if you stay in a hotel, the hotel will ask for your passport and do it for you.

We sit down at the police station, not at a desk, but at a meeting table where we are served another round of strong tea. The green tea drunk in Việt Nam (in the North, anyway) is especially bitter-tasting, strong and dry, and is never sweetened. My counterpart translates again as the police officer asks a series of questions about the purpose of my visit and how long I'll be staying here. The answer of "two years" is met with surprise, as well as a little bit of consternation. My visa is only for one year, and he doesn't know how he'll square that up in his report, but I tell him we have to get a medical checkup to get it renewed each year. Bureaucracy.

Satisfied, he makes me a genuine offer of community support. I won't have hot water to shower at the school this week, as my room is still being finished. But I'm welcome to shower at the police station anytime.

We walk back the short distance to the school, down a dusty dirt road that I will soon walk down every day, destined for more rounds of toasting tiny cups of tea. But before we get back to the front gate, a student spots us over the wall from a third-floor landing. "Hello teach-er!" he shouts with the vanishing 'r' of Received Pronunciation. Some more kids rush over to the railing to shout and wave to me.

By the time we are walking through the gate, it is time for the class period to end, and a booming drum sounds from the guard house. Vietnamese schools usually use a massive drum rather than a system of bells, and this is the first time I've heard it. It is startlingly loud.

Soon every class has emptied, not because the students are going anywhere, but because they've all rushed out to see what they know the first students were shouting about: they have come out to see the new teacher.

Hundreds of students are crammed into the three levels of hallways shouting and waving at me like I'm a celebrity. I smile and wave back, but I suddenly feel daunted. I have a lot of expectations to live up to.

Peace Corps Service Week 1 - Christmas Week 2024

About 6 weeks later, I return to my school and move into a room in a newly renovated building. I feel very grateful for what I have; not only is it far above Peace Corps norms around the world, it has many amenities that other volunteers in Việt Nam do not have. Although I don't need it yet, there is an air conditioner. I have not one but two wardrobes, which double as a room partition. And I won't have to filter the local well water for drinking, because the school has 10-gallon jugs of filtered water delivered to every room and I will be able to have one of my own.

I have even been given a carafe that keeps water hot for making a pot of tea (or perhaps, a cup of instant coffee?) on demand 24/7.

Settling in still has its challenges. My hot water heater does not work for the first week, and my cooking area is small. I have to cook most of my meals and keeping the room ventilated and free of odors is a challenge. I buy a small washing machine online for clothes, but the local plumber can't install it properly with the connections available. So, a larger used washer is purchased locally and installed. This one soon floods my room with water. The janitor tsks and moans as she helps me sweep water out my front door, "Cuh-ris... Ô'i giời ơi...." (Pronounced: "Oy zoy oy")

These growing pains lead to an emotionally difficult Christmas. The reason the Peace Corps Việt Nam sends us to site in mid-December is that it will give us about a month before our work should really be starting. Schools are reviewing and taking mid-term exams and then reviewing and re-taking them; the next semester doesn't start until mid-January.

This extra time is great for settling in, but it also means these were the loneliest weeks of service, right after a time when we were surrounded by friends. The frustrations of arranging a new room and starting a new lifestyle only added to a slight seasonal depression.

But the students and teachers went to great lengths to make me happy during the holiday week, when school remains in session. The students all know and love American pop Christmas songs and are eager to learn more about holiday traditions that they can take part in.

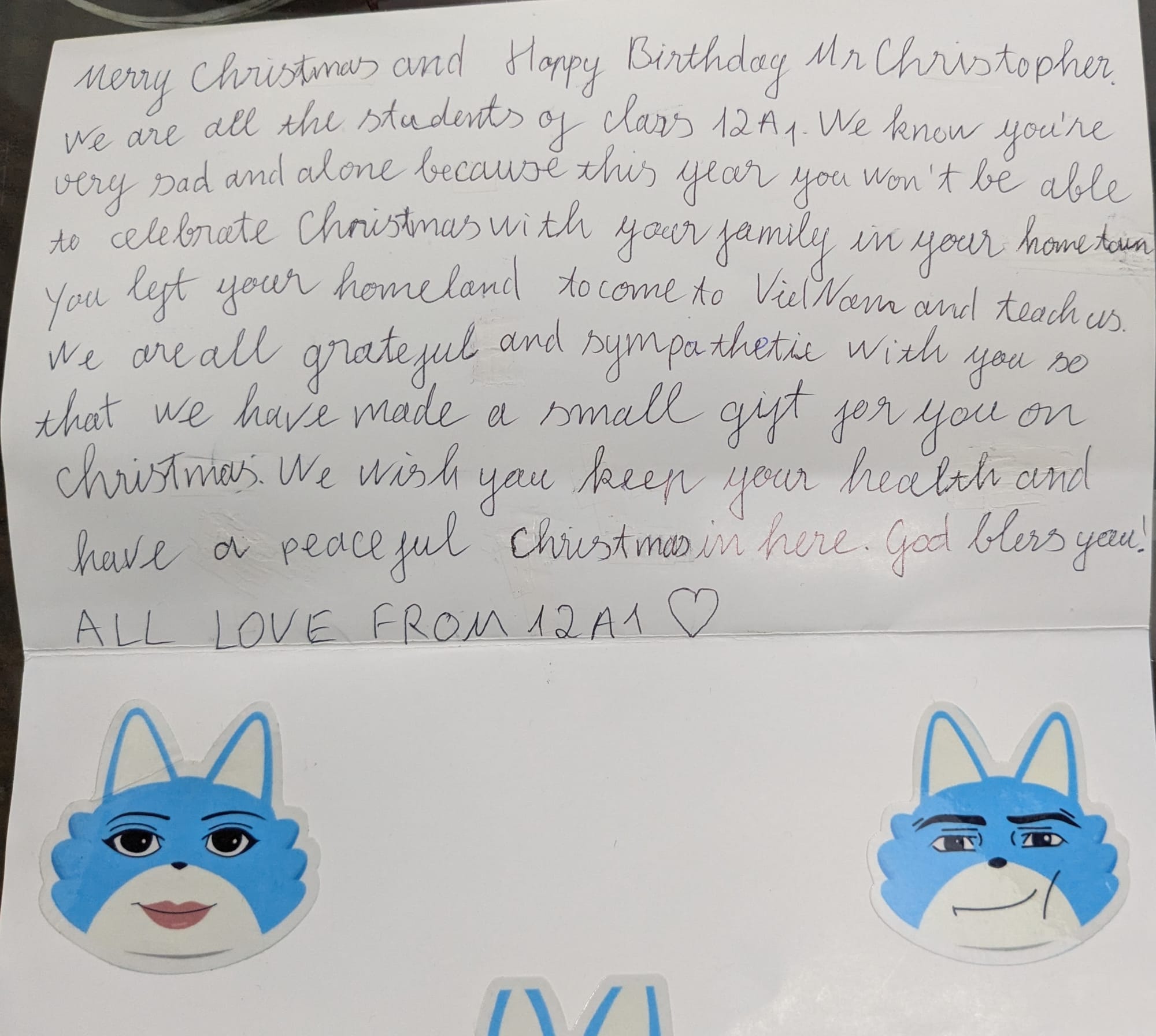

An entire class of seniors show up to my room without warning on Christmas morning. They cram into my small room to sing a Christmas song in English and present a gift-wrapped box with a bow on top. In the box is a motley collection of snacks and sweets - seemingly whatever the class could contribute from what they had in their backpacks at the time.

My birthday happens to be the day after Christmas, so the next day two more classes pay visits with full-sized, home-decorated birthday cakes, making me don a giant, conical birthday hat while they sing Happy Birthday. Then, I try with desperation to cut each cake into about 50 small square segments so that everyone can have a piece.

Birthday cakes are very popular here. Every village has a shop that can make them, and they taste exactly like American cakes. But the single "candle" they often affix on top might more accurately described as a small firework, shooting a spray of sparks.

Việt Nam uses both the solar and lunar calendars, and while the lunar calendar holds the most social significance, business is conducted on the solar calendar to match the rest of the world. So while New Years' Eve was not a huge event, it was an occasion for the principal to treat the teachers to lunch. It seems to be nearly once a week that they find something to celebrate and take the school staff out to the local restaurant. (Yes, "the" restaurant.)

But this time, a coach van comes to pick the teachers up to drive us 15 minutes to the nearest city. For this occasion, we are being treated to a restaurant that specializes in goat meat.

Vietnamese people like to ascribe special characteristics to eating certain meats and it is explained to me that eating goat today will ensure that we have good health and strength in the New Year. To that end, the meal begins with a serving of bright red tiê't canh: raw blood pudding.

While I am an adventurous eater and willing to try it, I was given instructions by the Peace Corps medical team not to eat the dish due to the rare but violent health consequences that can arise from parasites or improper food-handling. Thankfully, my English-speaking colleague is present today, so I don't have to struggle to get my point across that I am not allowed to eat this dish raw.

My new friends have a solution that will make "everyone" happy: they spoon my gelatinous disc of pudding into the roiling hotpot to cook it for me. After a few minutes, I am presented with an unappetizing grey-brown sludge. Not eating it hasn't occurred to my eager hosts. Fortunately, it's not too gross. Actually, with the unusual garnish of peanuts and mint, it's kind of tasty.

Two 1-liter bottles of "Aquafina" were brought by the teachers from the school and these are now passed to either end of the table, the contents emptied into a bowl which rests in another bowl of ice water. Thus begins the ritual of drinking Vietnamese rice wine.

Lunch, dinner, even breakfast, it's always a good time to build your relationships with your colleagues by giving them a toast. The youngest person at the table usually keeps everyone's shot glass filled via a scooper with a very long handle for reaching across the table. You can't drink unless someone makes a toast, but you won't have to wait long.

If someone toasts to you personally, you drink with them and then shake their hand. But if the whole table drinks together, everyone stands up, putting hands on top of each other in the middle of the table to chant "Một – Hai – Ba – dô!" (Or "1-2-3-cheers!" The last word is pronounced "zo" in the North.)

My head English teacher looks at me knowingly at the beginning of the meal as my cup is filled: "Chris. Remember? You are not allowed to drink."

"That is not the rule!" I protest.

However, I allow them to fill my little glass only halfway full, because things can get out-of-hand by the end of lunch with teachers. The wine is home-brewed and then the clear liquid is sometimes steeped with different herbs or tree leaves until it turns an amber shade. I have tasted many different flavors, but I have never been able to learn any of these flavoring ingredients - many of them may not even have English names. Starting at 14-17%, after some evaporation, the aged wine sometimes tastes like it could be around 20% alcohol.

I drink judiciously; I don't usually have classes in the afternoon, but I don't want to be completely useless for the rest of the day either. At the end of lunch, the toasts come fast and furious, as people from other tables come over, red-in-the-face but with wide smiles.

At the end of the meal, some of the older male teachers regard their new American colleague suspiciously. "Do you feel happy?" one says in stilted English. "Yes! Very."

Another one says something into Google Translate. The phone reads: "Drunk?"

"No, no! Không!" They all laugh.

I realize later, it's probably the wrong word to use for "no" in this instance. They know what I mean, but it sounds funny. Không has a connotation closer to "nothing"; while another word for "no" - chưa - means "not yet".

The principal says something about me in Vietnamese; another teacher translates: "He says you are very good at drinking Vietnamese wine."

Thanks, I think?

On this day, there will be no karaoke (phew!), but Vietnamese people also love to take pictures together. In the lobby of the goat restaurant, a large Christmas tree is still standing next to an ostentatious display of taxidermied mountain goats on a fake mountain next to a pond of real water. The teachers all shake my hand and want to have their picture taken there with me.

I can't help but grin widely. As has happened often through my first weeks and months of service, I am overcome by a sense of surreality: it is all so weird and wonderful that it's hard to believe what my life has turned into.

I think I have a great team and community to work for in 2025.

In fact, you could say we've already been "goated".