Living in Việt Nam, Pt. 2 - You Will Survive Now

It's my turn to book the Grab, and when the tiny hatchback car screeches to a halt I jump in the front seat. Grab is Việt Nam's answer to Uber, a taxi-hailing app with an interface that can be set to English, and in which you can also order food and groceries to be delivered by motorbike for astonishingly low delivery fees. My housemates and Thùy - our language and culture teacher - squeeze into the back seat.

"Oh, look Chris. You're in the hot seat this time," Andrés taunts playfully.

Thùy nods in agreement. "Talk to the driver." She says it in a low monotone voice: her playful mimicry of an American accent. It sounds vaguely threatening.

I turn to the older gentleman in the driver's seat, who has whipped the car into the oncoming lane to speed past a motorbike. His skin looks taut and weather-worn and his teeth slightly yellow; he would be past retirement age in the United States, but he still looks spry.

"Anh tên là gì?" (What is your name?)

He steals a glance my way, surprised, and the laugh lines deepen around his friendly eyes.

"Chú tên là Trùng."

He pulls around a car stopped at a red light and merges seamlessly into the traffic with the right-of-way. Although his Grab vehicle doesn't have taxi signage on the outside, it has the yellow license plate that differentiates it as a commercial vehicle and gives it a higher position in the traffic pecking order.

"Em tên là Chris," and then I pause to struggle to put the words for 'pleased to meet you' together: "Râ't vui được gặp anh."

He chuckles and repeats it, correcting me. "Râ't vui được gặp chú."

This time I hear it: he is correcting the pronoun I should use to address him. It has been my single hardest obstacle in learning Vietnamese: using the correct pronoun. In any given sentence, you have to acknowledge your relation to whom you are addressing in terms of both age and gender. I had chosen to address him as my older brother (anh), but he is a full generation older than me so he thinks I should call him uncle (chú).

This is practically my worst social nightmare, coming from a culture where I would never judge or comment on how old or young someone is, much less make a big deal about their gender. It's even worse in an unfamiliar country where my guesses on how old people are can often be a decade or two off!

But Chú Trung is not offended, and he's not asking me to show him more respect. I probably have more leeway for making mistakes since I'm a foreigner, and I'm clearly only a few days into learning the language. But mainly I think he is just telling me the fact of the age, using a structure that is built into the language.

In the first week of meetings at the Peace Corps offices when I first started to say hello to the Vietnamese staff by name, I thought I would be able to get away with addressing most of the women as older sister (chị), not because they are older than me but because I am there to look up to them for guidance during training. But they quickly giggled and corrected me: "No, no, no! You have to call me em!"

Later, we got to know the matriarch of a family that runs a fried rice stall that we go to regularly. It turns out that she is the same as age as me.

"So, what do I call her?" I ask Thùy.

She thinks for an alarmingly long time: "Hmmmm. I think you can still call her Chị because she looks older than you." (Me: "Noooo...!")

We get to the edge of Phô' Cổ - the famous Old Quarter of Hà Nội - and hop out of the car to a picturesque view of Hoàn Kiê'm lake with its fairytale red bridge. The streets are swarming with tourists but also Vietnamese brides taking pictures with the tiered pagoda in the background, as the sun sets warmly on the cultural landmark.

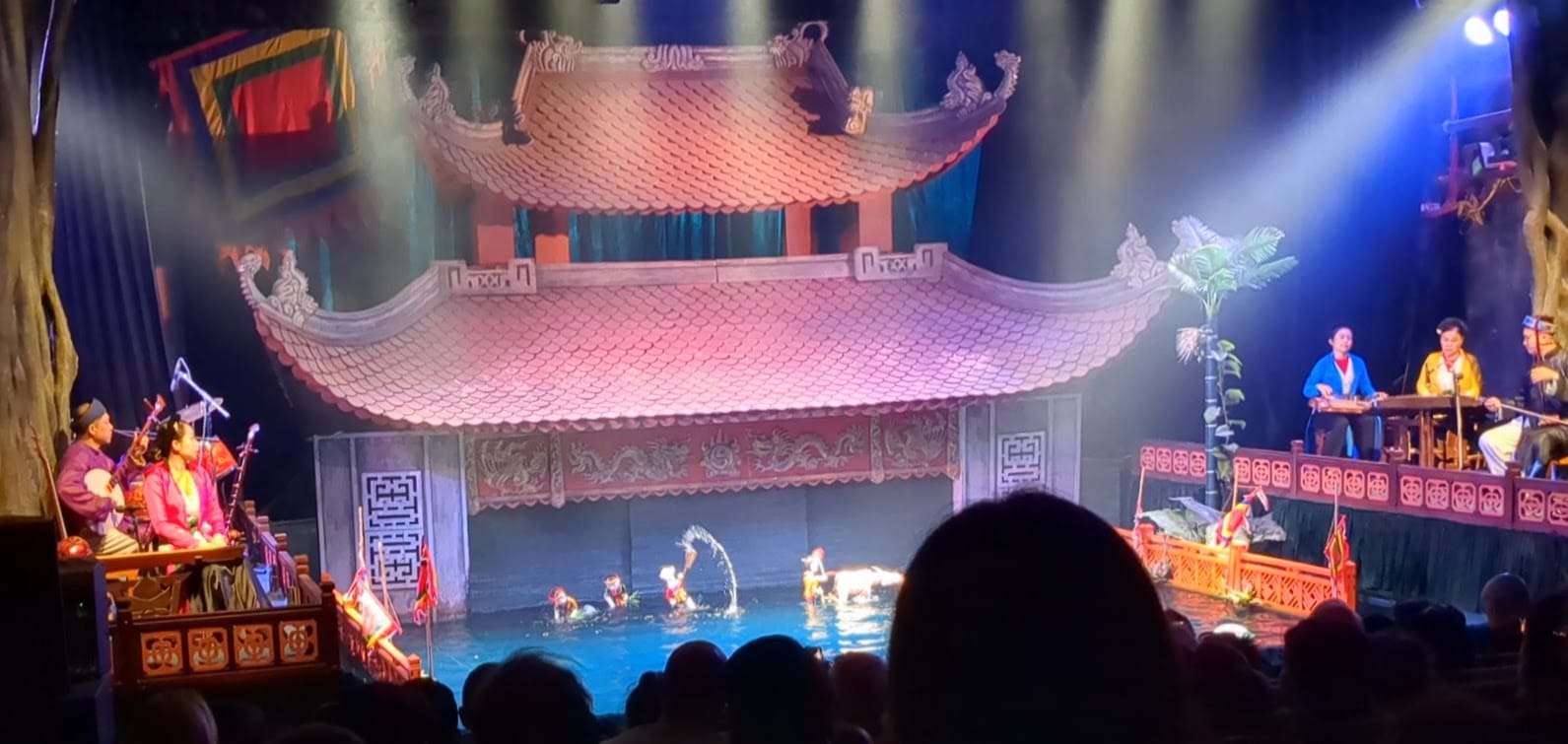

A crowd has formed around a dozen small girls in matching outfits, a dance class whose instructor leads them through several Vietnamese pop routines for the tourists. But we soon see more Americans we know: all 20 of us have met up, as the Peace Corps has bought an entire row of the intimate and historic Thang Long Theatre, the home of Hà Nội's world-famous water puppet show. Other tour guides can be seen holding up flags outside the entrance; it is a must-see for any tourist, and the 45-minute show starts every hour.

The stage is submerged in a couple feet of water, while musicians and singer/narrators are arranged on raised platforms on either side. An ornate pagoda provides the backdrop; the black curtains of its entryway hide the puppeteers, who operate puppets on the end of long poles who emerge out of the water in front of the audience. Puppet people row boats across the stage as fish jump out of the water near them. A dragon dips in and out of the water with a waterproof firework providing a spray of sparks from its mouth. The artistry of the show impresses all of us.

The show displays a number of scenes of Việt Nam's paddy field agriculture and daily life, including an emphasis on the importance of education, but also classic myths from Vietnamese folklore, such as Hoàn Kiê'm Lake itself. While the classical music of Vietnam has roots in Chinese music, the declining artform of water puppetry is distinctly of Vietnamese origin. Thùy had never seen the Thang Long show before - being new to Hà Nội herself - and afterwards she tells me it filled her with pride to be Vietnamese.

When we get out of the show, night has fallen, and the Old Quarter is packed with both locals and tourists. It is Saturday night, and the Old Quarter is a paradise for shopping and people watching and eating street food. The most prominent street foods are fresh fruit and xúc xích - sausages grilled on a stick for eating on the go. But the sausages here are heavily processed, looking like chubby hot dog weiners, so we hold out for more "exotic" (to us) fare.

We dine on phở cuô'n (like "spring rolls" - beef and herbs wrapped in rice paper), nem rán (like spring rolls that have been fried crispy), and fried pastries stuffed with meat or shrimp, all for fractions of a dollar per piece. One health-conscious volunteer orders 10 nem lụi - minced pork and herb patties skewered on stalks of lemongrass for grilling - and our waitress feigns disbelief. No one has ever ordered that many pork skewers. But the skewers are not loaded up like shish kebabs; by American eating standards, there are only about three "bites" of meat per skewer, and any of us could finish ten easily.

When we are done, Hùng, one of our other language & culture teachers comes by our table and asks if we're ready to try trứng vịt lộn. He's really passionate about the common Vietnamese snack, but only three of the 20 volunteers have expressed interest in trying it. You can probably already guess that I am one of them.

Trứng vịt lộn is a fertilized duck egg where the embryo has started to form; in the US it is more commonly known by the Filipino word for it: balut. Every neighborhood seems to have a vendor for it here, so I thought I would it try it with a guide who could show me "the proper way to eat it."

We set out after Hùng, who darts into the crowd with surprising speed. He seems to know he is losing us, because he sets his smartwatch to flash a bright light and sticks his arm into the air like the flag of a tour guide.

We come not to a stall or a food truck, but the opening of an alleyway, and sit on the bright pink plastic stools there, and a grandmother comes forth from the alley and stands next to the sign that gives the price for her trứng vịt lộn. We order several and ask her if we can have a round of beers too, and before you know it she comes back from the store next door with several beers in a grocery bag. In Viet Nam, if you ask if they have something, you will get it if it is sold within a certain radius.

The eggs come peeled in a small bowl with about an ounce of mild, sweet liquid. It looks like a mutant hardboiled egg with veins bulging out of it. Hùng demonstrates the proper garnishes of herbs, fresh chili and salt. The yolky part is very dry and parts of the egg are toothsome with cartilage - a texture I have already gotten used to; the Vietnamese don't waste any edible parts of the animal.

While most of the experience of eating this egg was less than pleasant for me and my fellow Americans - like eating an egg that was drier and more chewy - there was one tender bite in the middle that had the rich flavor of organ meat like liver. I could try to justify eating trứng vịt lộn on those terms. But I think that the Vietnamese food culture values eating certain things for specific health benefits. Some of these benefits are supported by modern science - cartilage is prized as a source of collagen in the diet - other benefits seem to be more attributable to folk wisdom.

Next, we head to a famous spot for eating snails; the tables for this one restaurant stretch down both sides of one street for half a block - in front of other businesses which are closed for the evening - with as many as a dozen people hunched around the small plastic stools as makeshift tables. Bowls of snails or clams come in a highly aromatic broth with herbs and lemongrass. You are given little shards of sharp metal with which to skewer and cut free the fresh snails from their shells.

The atmosphere in the Old Quarter on a Saturday night is crowded and high energy, but also somehow laid back. Entire Vietnamese families are out and about; although there is some threat of pickpocketing, on the whole it feels very safe. There are free concerts going on at several street corners; at several points, Hùng identified a "famous singer" or a "contestant on Vietnam Idol" going on stage for a song, just as we happened to be passing by.

One street corner, having been shut down to traffic, has turned into a dance floor for ballroom dancing. Street performers do acrobatic tricks or urge passers-by to jump rope. Strangely (to me), I don't see tip jars out for any of the performers; the singers, at least, seem to be doing this as promotion. Maybe some are being paid for by a city tourism organization. I am not one for big crowds or festivals, but I find the atmosphere is very charming.

The next morning, Sunday, I awake with a mission to finally do some clothes shopping. I flew to Viet Nam with only one checked bag and a carry-on; I only have about 7 full outfits.

Thuy has volunteered to drop me off at a shopping mall on her way to her destination on our day off. There is a fancy five-story shopping mall in the West Lake district, with tons of designer fashion outlets, but little affordable shopping. I'm hoping that heading 10 km east into a more typical neighborhood of Hà Nội will give me some more affordable options.

The mall is filled with Japanese brand stores, but the clothing itself is made in Viet Nam. It seems cheaply priced by American standards, but the lightweight clothing also doesn't seem like it will last very long. I ask Thuy if the prices are good for Viet Nam, but her nose crinkles. "I think you can find cheaper."

Thuy suddenly announces she is leaving, as I try to determine whether I will fit into the largest of only three sizes of pants on offer.

"Anh Chris! I'm going. You will survive now!" she says cheerfully.

It leaves me in fits of laughter. She has given me a mission to find my way home on the bus after shopping. It's her way of expressing to me that she now has confidence that I have enough "survival" Vietnamese to get home easily.

I manage to figure out my pant size and also find really cheap dress shoes ($320k D, or $13 USD). I pay with my American credit card; although I have a Vietnamese bank account, they have strict laws on knowing where deposits come from, so I haven't been able to deposit much in it yet except from small transfers directly from friends for paying for them at restaurants.

Most places don't take cards here, but even the smallest mom and pop joints have a QR code to which you can initiate a bank transfer directly to their account. This seems to be a fee-less system, and it's super convenient. "Venmo" but at a national level. I can also buy nearly anything - groceries, movie tickets, or a taxi - directly from my national bank's app.

My shopping successfully completed, I head out into a light drizzle. A taxi driver sees me looking around for the bus station and tries really hard to get me to take his cab. But I'm on a mission.

I find my bus, and determine that the mall is its final stop, so I don't have to worry about getting on going the wrong direction.

The bus driver is all smiles as I board an otherwise empty bus. Having ridden another bus here, I think there should be another employee here to take my ticket; the driver is almost completely blocked from me by plexiglass, so I know he doesn't usually handle the cash.

I sit close to him, and he says several things to me in Vietnamese. Despite my training, I don't understand anything. I tell him I only speak a little, and I don't understand. He just laughs heartily.

We stop at a major intersection, and he takes out a thick glass pipe about a meter long. It is a water pipe, basically a bong, for smoking tobacco. He takes a big hit off of the pipe and exhales out the open window of our empty bus. He then offers to pass the pipe to me over the plexiglass. I smile and wave it off: "Không, cảm ơn anh." (No, thank you.) He laughs hard. Even if I smoked tobacco, the water pipe would be dangerous; American smokers have been known to pass out from the strong rush of nicotine it provides.

At the next stop the ticket taker gets on, having stopped at a food stall. Well, I think he's the ticket taker. The only thing that looks official about him is the clipboard he is holding. The last bus I rode on in Hà Nội was a very nice bus run by a private company. I must be on a public bus now.

The ticket taker sizes me up for a minute, or perhaps - I realize - he is trying to figure out how to ask me for the fare. I say in Vietnamese, "It's $7,000, no?" He corrects my pronunciation, but we complete the transaction as I have exact change ready. We try to have a conversation for a while; the first thing he wants to know is how long I've been in Việt Nam. I've only been here for three weeks, but I will be here for two years.

We soon deplete all of the Vietnamese I know, and I tell him I only know "a little bit of Vietnamese". He repeats this to the driver - "một chút tiê'ng Việt!" - and they both laugh warmly. I try to tell him the name of my street, and he doesn't have any idea what I'm saying until I correct my pronunciation of one little vowel.

The bus ride back home takes about an hour. I end up meeting a Nigerian who eagerly sits next me to practice his English. He says he has been here four months. At first, he tells me he is here on vacation, but then he starts to lament that there are no jobs for foreigners except for English teachers like me.

I try to ask him about what he likes to do around town, hoping to get recommendations about things to do or foods to eat. But he doesn't seem to understand and keeps complaining that there are too many motorbikes here. I try to persuade him that maybe it's better than everyone having a full-sized car. He simply says: "No."

"In Cambodia, it's not as bad as this."

"Oh, you've been to Cambodia too? Do you like Cambodia better?"

This makes him smile. He smiles as if to say: you can't trick me.

"No. Việt Nam is better."